A Discussion of Bourgeois Equality Chapter 26 “And so does the Word ‘Eerlijk’”

In many ways this chapter is similar to the previous chapter that traced the change in the definition of honest to show how culture was changing.

In the 1500s and 1600s, McCloskey says honest meant aristocratic and noble. But as the next few hundred years passed, the rise of the bourgeois class shifted what the culture valued and that shifted language.

Honesty became associated with truth-telling and reliable and became a virtue for the common man to aspire to.

Now, Dr. McCloskey is adding to that point in this chapter by showing the shift is seen in languages other than English as other countries were also becoming more warm to the rise of the bourgeois. Further, she suggests you see this shift in a country whenever it begins to value trade tested betterment.

Excuse me, ‘eerlijk’?

In many ways the first part of the chapter is a rehash of last chapter, just applied to different languages so I don’t want to bore you with too many examples.

What this chapter does add is that the shift in the definition of honest from being aristocratic to bourgeois occurred also at a similar time in the non-English Germanic languages. (p. 247)

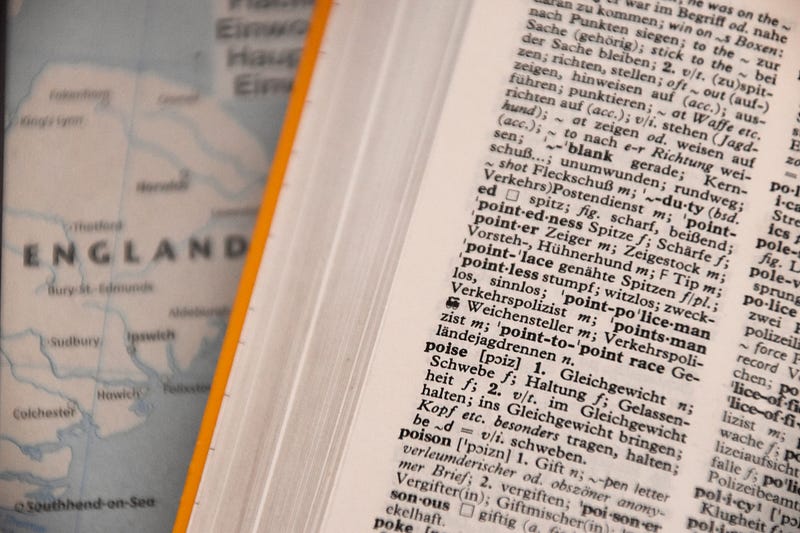

The Dutch ‘eer’ and German ‘ehre’ still nowadays mean ‘noble, honorable, high-status, aristocratic’ — like English ‘honorable’ when used among would-be aristocrats on the dueling grounds … But in Dutch and German the addition of ‘-lijkl,’ ‘-lich,’ (-like) yielded an ‘eerlijk/ehrlich’ that eventually comes to mean simply ‘honest,’ in the same sense as the modern English commendation of truth-telling necessary for a society of merchants to work. (p. 248)

Why are we studying words? I thought this was economics

McCloskey’s overall point in her book is that the Great Enrichment of the past couple hundred years is not just better use of capital as the name capitalism suggests. Instead it is a cultural shift that esteems the dignity of the common man, setting him free to follow trade tested betterments that ultimately lead to the explosive growth in wealth.

She says she has faced criticisms for looking to language as evidence. For one thing, aren’t there writings that sneer at the bourgeois past the 1700s? Isn’t she just cherry-picking examples?

In any age one is going to find praise or blame for bourgeois virtues, and vices, somewhere. The charmingly passionate old men peddling copies of the ‘Socialist Worker’ on street corners will be glad to tell about the vices. The questions are: What [is] the ratio of praise to blame found in documents that are salient or honored or revealing? Does it change? And does the change matter for betterment? (p. 253)

While I do find it an unusual piece of evidence as an economist, I think she raises a good point by examining it. Essentially, when trade tested betterment was not in existence, when society was in a more feudal state, we did not really need a word to describe “good” market behavior.

But as the merchant class grew, and as attitudes towards profits became more positive, we do need a work like honest to be a virtue for the common man to aspire to.

Thus the change in attitudes is changing the language. And the change in language can be examined to see what people value.

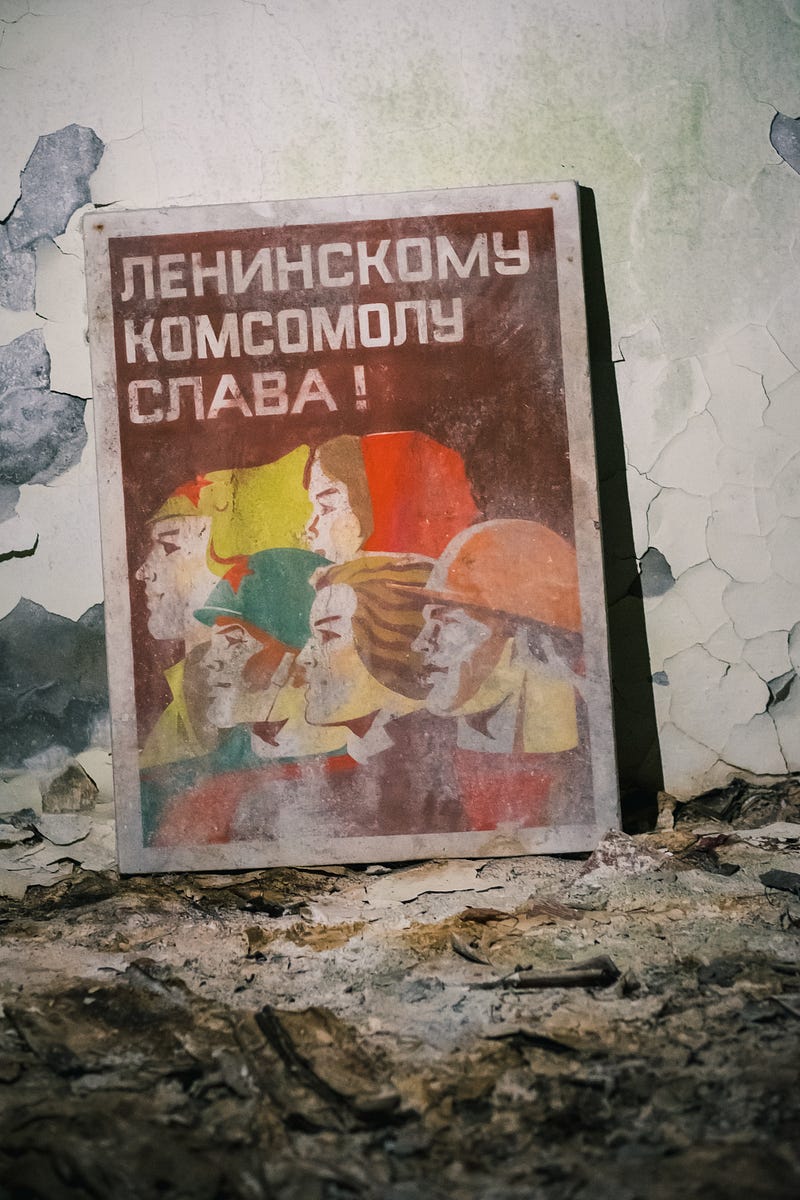

She offers a more recent example of this in India. Upon independence from Britain, India moved in the direction of modeling their economy after the Soviet Union, rejecting all that trade-tested bourgeois British-ness.

Their economy stagnated in the 1970s and 1980s leading to market reforms by 1991 not long after the USSR fell. McCloskey says you can see the cultural shift in the language that enabled the political change.

Apparently Mahatma Gandhi thought buying low and selling high was “disgraceful,” and Nehru stating profit is a bad word. (p. 254) And yet, from that anti-bourgeois basis, movies provide a glimpse into cultural changes.

Nimish Adhia has shown that the leading Bollywood films changed their heroes from the 1950s to the 1980s from bureaucrats to businesspeople, and their villains from factory owners to policemen, in parallel with a similar shift in the ratio of praise for trade-tested betterments in the editorial pages of the ‘Times of India’. (p. 254)

McCloskey suggests that the 1991 pro-market reforms would not have been possible without this “change from hatred to admiration of trade-tested betterment.” (p. (254)

These reforms liberalized the economy and took growth from 1% to 7% showing how a shift in attitudes allowed trade tested betterment to begin, resulting in economic growth.

Clearly without some sort of change in opinion the Congress Party would not in a democracy have been able to liberalize the economy…I am making for the Great Enrichment the same case that Adhia made for late twentieth century. (p. 254)

Conclusion

We saw last chapter that a shift in the words used in English reflected a new, more positive attitude to trading, profits, and the bourgeois class that was on the rise.

The evidence in this chapter strengthens that observation by showing a similar shift at that time in the non-English languages when they saw a rising bourgeois class.

In some ways, the most compelling evidence to me is seeing that shift again in India some two hundred years after the Great Enrichment as they have gone through a similar shift towards liberalizing trade.

For trade tested betterment to take root and become the Great Enrichment, society needs to value the virtues that support it. Looking to changes in the use of language shows us this values shift.

Reference: McCloskey, Deirdre Nansen, 2016. “And so does the Word ‘Eerlijk’,” Chapter 26 of Bourgeois Equality, The University of Chicago Press.