A Discussion of Bourgeois Equality Chapter 48 “And Betterment, Though Long Disdained, Developed Its Own Vested Interests”

Change is hard to do in a system in part because it hurts one or more groups who are part of the existing status quo. So how can something as big as a shift from respect for elites and hierarchy towards respect for the common man and his ideas take root?

Earlier in the book, Dr. McCloskey shows how the British thought about people in the Elizabethan era before the Great Enrichment.

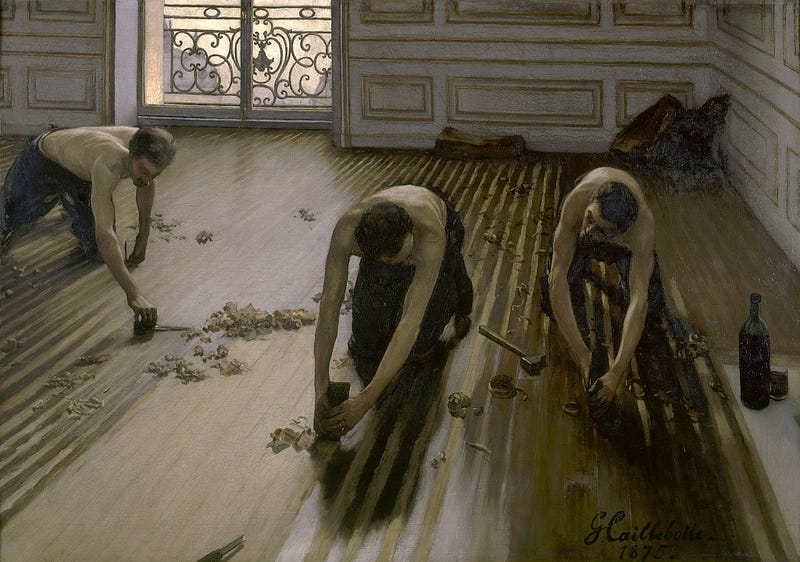

You were born to a position and you stayed in the position. Those at the top were born to it and deserved it. There was no room for someone at the bottom with a good idea to run with it.

But as ideas and rhetoric shifted in favor of the bourgeois as she has been showing us in the previous chapters, a rising class of merchants grew.

And what really matters from that story in this chapter is that process created new vested interests in the continuation of the system that respected the Bourgeois. At least in Britain in the 1700s.

However, a rising bourgeois class is not a guarantee of establishing the process of the Great Enrichment. They are still people and can be just as selfish, and short-sighted, as any of us.

Not that the bourgeoisie is to be trusted entirely to welcome betterment or novelty, then or now…True, a small society of businesspeople protected by the state could itself rather easily set up obstacles to betterment, by arranging for local monopolies. (p. 459)

This is what McCloskey says happened in Venice and Florence in the 1200–1400’s when they were successful trading societies enriching a merchant class.

Yet, they then turned to monopoly protections with guilds that choked off the Great Enrichment. Why? The bourgeoisie that had already been created began to aspire to become aristocratic and thus put up roadblocks to keep any future common man with a good idea from rising up.

Those were places where mercantilism got its first toehold, replacing the feudal system, but neither system was comfortable with the disruption that is required for a trade tested system of betterment to work.

Mercantilism did free people from the static feudal system it replaced and allowed a rising merchant class like in Venice and Florence. But both systems shared a zero-sum view of the world.

The trade-tested system of betterment that created the Great Enrichment sees the world as a place where everyone can be better off.

That is what allows us to tolerate the necessary disruptions of technological improvements because even though there are winners and losers in the status quo, all will be made better off as standard of living rises.

It is a view that you can grow the pie, not just redistribute a fixed pie.

But change is hard because it does cause disruption and uncertainty, and people do not like any of this so time and time again, the idea of central planning keeps returning.

Oddly, people who would readily agree that attempting to lay down the future would be disastrous in, say, painting or rock music or journalism or most science and all writing of novels or of scholarly books, think that we already know how to organize a mere economy, and that the government knows best in central planning or regulation or nudging. (p. 463)

A famous essay by Leonard Read, “I, Pencil,” captures the complexity of the economy in producing a seemingly simple product like a pencil. Central planning makes a mess of that.

Given all that, why did the trade tested system of betterment take root in England in the 1700s, given the disruption to the social order and the entrenched elites?

After the change in rhetoric around 1707 a free-trade area as large as Britain’s could develop sufficient material and intellectual interests in free trade to unbind Prometheus. A balance of the interests against the passions, in other words, is not merely a modern liberal fancy. There grew up in Britain during the eighteenth century a group of interests which had by then a stake in free trading at home and abroad, and all the more so eighty-two years after 1707 in the expanding free-trade area of the United States. (p. 464)

In Britain then at that time, the merchant class that had been growing became a vested interest in preserving the trade tested system of betterment. And unlike in Venice and Florence, this occurred after a religious cultural shift.

And it was buoyed by technological changes like the printing press that could spread new ideas.

A change in rhetoric allowed those who had a vested interest in continuing the trade tested system of betterment to triumph over those who wanted to cement their new standing with monopolization or to put themselves in the heady position of planning the economy.

When the new rhetoric gave license for new businesses, the businesses could enrich enough people to create their own vested interests for opposing a mercantilist plan for local greatness through monopoly…Such new interests in the past few centuries have bred toleration for creative destruction, and for unpredictable lives, and for most children having much more than their grandparents. (p. 465)

Again in this chapter, we can see McCloskey’s inspiration for writing this book. A change in rhetoric created the Great Enrichment and thus a new change in rhetoric could undo it.

Given the tendency for those in the winning positions at any point in time to put up the fences with monopolization, if we do not have the proper enforcement of antitrust laws to stop them, our apparent free trade system will deteriorate into an unbalanced and unfair system where the common man with good ideas cannot rise up.

If we then mistakenly view this outcome as a result of the trade tested system of betterment instead of a corruption of it, then the anti-bourgeois rhetoric can take hold and take us backwards into an authoritarian, planned system, with all the wealth in the hands of the few and none for the rest.

Essentially this is the neo-feudalist system that seems to be pushing into our world today.

Reference: McCloskey, Deirdre Nansen, 2016. “And Betterment, Though Long Disdained, Developed Its Own Vested Interests,” Chapter 48 of Bourgeois Equality, The University of Chicago Press.