Part 2 of a Discussion of Peter Foster’s Why We Bite the Invisible Hand Chapter 4 “Dark Satanic Minds”

Last blog, we learned about one of the Utopians, Robert Owen, that rose up to challenge capitalism because of all the social upheaval wrought by industrialization.

A more famous challenge, and one that persists to today, came from Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, himself a cotton manufacturer, in the Communist Manifesto written in 1848.

Some of the errors included in the Manifesto were also a part of our primitive understanding of economics at that time.

David Ricardo contributed a lot to modern day economics with his understanding of comparative advantage that recognizes we all benefit from trade because each person or country is going to be relatively better at some goods. If the one who is relatively better specializes in that good, total production rises and after trading all are better off than in autarky.

However, he also saw the economy as a “never-ending struggle between ‘factors of production’: land, labor and capital.” (p. 83) Today. we see the benefits of trade extends into the use of our factors of production. It is a system of mutual benefit, not a fixed-pie death match. However, this fixed-pie struggle played a large role in Marxism.

The dominant voice for this fixed-pie view came from Thomas Malthus who thought we were doomed to forever have our population growth outstrip our ability to produce. While he had been correct up until the time he was writing in 1798, he did not understand the power unleashed by capitalism to vastly expand our production even with the same resources.

One more error of the day incorporated by Marxism was the labor theory of value.

Ricardo and Adam Smith both fit into the Classical School of economics, as we refer to it today, and while they got much right, they held to the labor theory of value, which we later discounted.

Today, we know goods are produced using land (or natural resources), labor, capital, and entrepreneurship. Each of these resources need to receive a return to make it worth producing the good. Labor theory of value held that the value of a good was determined by the labor that went into producing it.

With this theory, something that takes 2 hours to produce should sell for twice as much as something that takes 1 hour to produce.

If this were true, and the labor is not paid as much for something that is labor intensive, you can begin to see where Marx and Engels get the idea of labor exploitation. However, as we later figure out, the price of a good depends on the interplay of supply and demand, not just the costs that went into making a good.

Marx and Engels

Engels is not as well known today, but his history shows he was every bit in line with hating capitalism as Marx.

Engels was a wealthy son of a successful German mill owner. His father sent him to England to oversee the Manchester branch of the business because he hoped it would “cure the young man of his revolutionary tendencies.” (p. 97)

Engels thought the mill workers in Manchester were ready for a revolution so he was happy to be there.

His first two years there provided much of the literary color and moral outrage that went into his most significant collaboration with Marx, The Communist Manifesto. That brief document, of scriptural importance in the war against capitalism, was in many ways a condemnatory snapshot of the Manchester cotton industry in the “hungry” 1840s. (p 97)

The Manifesto sees two classes: the bourgeoisie, AKA the capitalists or the business owners, and the proletariat, AKA the workers.

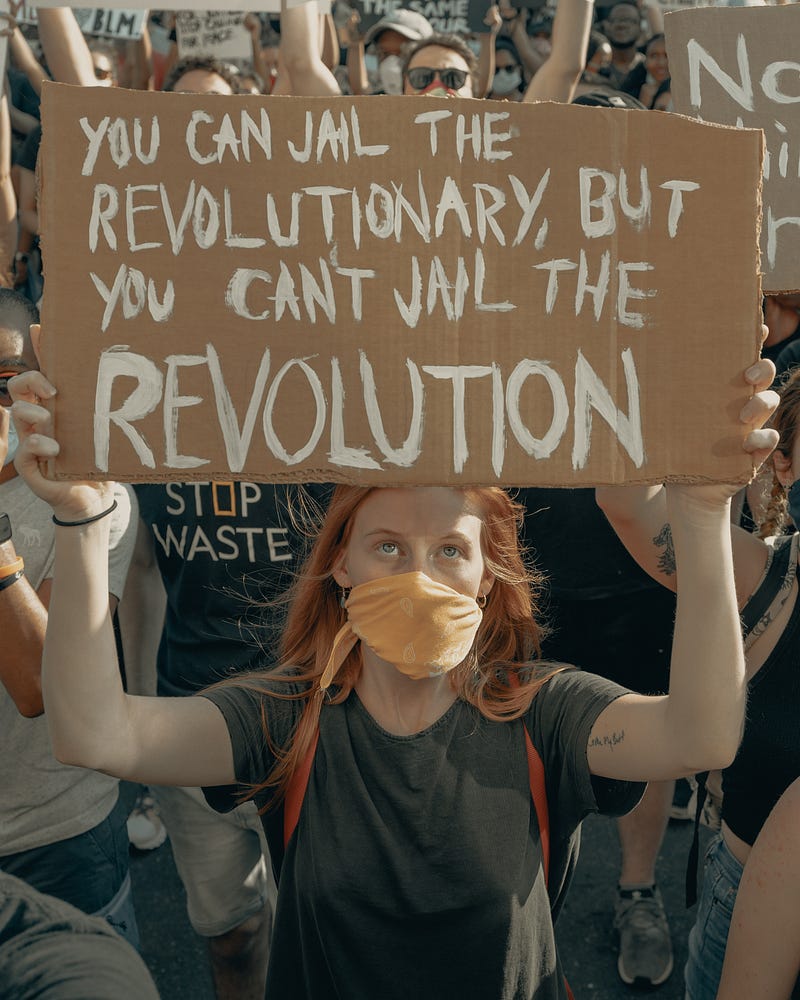

Marxism holds the bourgeoisie have all the power, and they exploit the proletariat. This exploitation would inevitably lead to the downfall of capitalism when the proletariat would rise up in revolution. Private property would be outlawed, and Communism would be established.

But the actual workings of Communism were spelled out only in the most vague terms. Communist society would — somehow — regulate “general production” and thus make it possible “for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner.” As the economic historian Alexander Gray noted, “A short weekend on a farm might have convinced Marx that the cattle themselves might have some objection to being reared in this casual manner, in the evening.” (p. 97)

Early industrialization and the social upheaval it caused was ugly, no doubt. You see similar fears being raised today at the beginning of AI technology rising up.

However, while I understand why you would have a reaction against capitalism as we see with the Utopians and Marxists, the Manifesto is supremely thin and intellectually vapid.

A privileged son (Engels) and a narcissistic power-mad intellectual (Marx) had a tantrum and dreamed up an alternative reality that would put them, or people like them, in charge.

They took Smith’s intellectually deep and complex analysis of human nature in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, and replaced it with a one-dimensional world made up of two kinds of people: the greedy business owners who used the power of the state for their own benefit and the exploited workers. (p. 98)

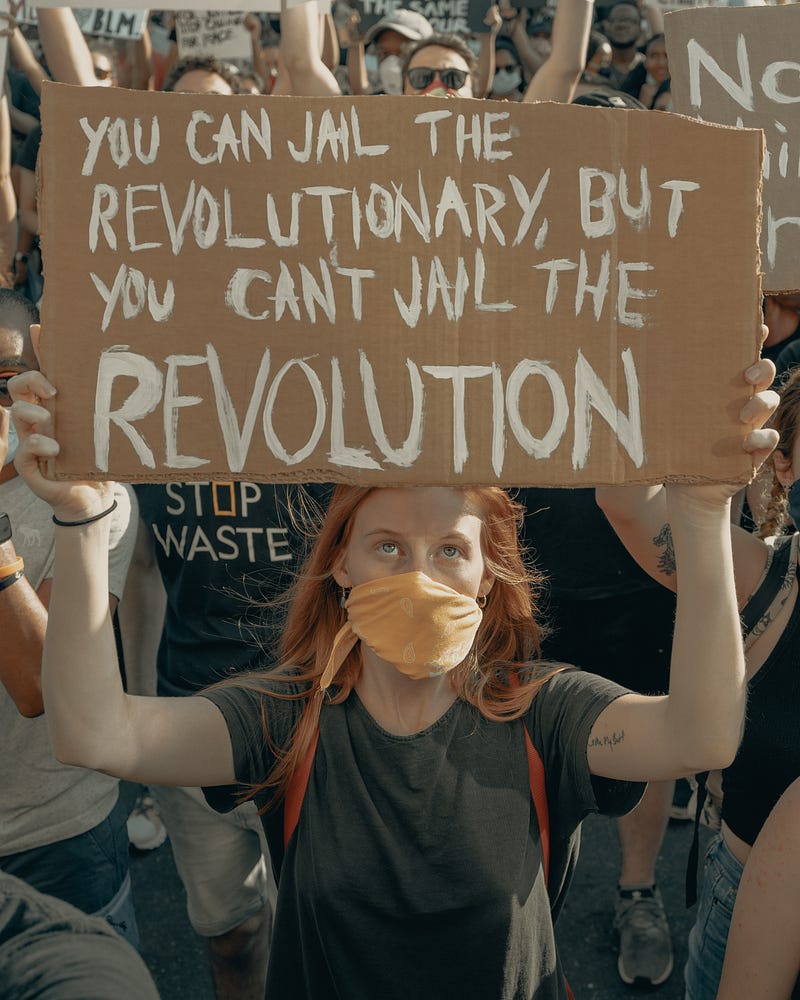

They asserted that this revolution would naturally happen and yet even in their writings, they acknowledged the need for force. From the Manifesto,

The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims…They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win…Workers of all lands, unite. (p. 99)

While there were several European revolutions in 1848, they were not influenced by the Manifesto that was just published in the same year.

And Engel’s hope for an English Communist revolution failed to materialize as well because real wages were rising for the “proletariat.” Much to their disappointment, the benefits of capitalism outweighed the problems of early industrialization.

Marx simply ignored or misrepresented this reality, holding firmly to his predictions of Communism’s inevitability. (p. 100) Sadly, as we know, their ideas were picked up by several regimes in the 20th century leading to millions and millions of deaths.

Marxism, once worked over by Lenin and Stalin, opened a Pandora’s box of social engineering whose damage would scar the 20th century, from the rusting industrial behemoths of the former Soviet empire, through the killing fields of Kampuchea, to Cuba’s island gulag. And yet despite the horrendous practical results of Marxism and the stunning achievements of free enterprise, capitalism still tends to attract the more vehement criticism. (p. 101)

Conclusion

While Soviet Communism died, the immature ideas of Marx and Engels live on. By the 1950s, it was rebranded in academia as critical theory, but at its root is the cardboard cut-out version of reality that there are two classes: the oppressed and the oppressors.

We see it today in critical race theory where in the U.S. white men are the oppressors and everyone else falls into the oppressed group, but at its root is this same Marxist thinking. It is a dark view of the world that leads only to violence and, they hope, revolution that will leave them in charge.

Once again, we need the collectivist Marxist thinking to lose to the reality of the benefits of free participation in capitalism based on mutual benefit. We need to move away from its Malthusian, fixed-pie view of the world that leaves us all fighting for scraps.

This chapter has been about two movements that were critical of capitalism. In the next chapter, Foster moves on to Ayn Rand, ostensibly a defender of capitalism. But as he notes, with friends like that, who needs enemies? Her views are another kind of cardboard cut-out version of reality that can be used by critics of capitalism.

Reference: Foster, Peter, 2014. “Dark Satanic Minds” Chapter 4 of Why We Bite the Invisible Hand, Pleasaunce Press.