Part 1 of a Discussion of Peter Foster’s Why We Bite the Invisible Hand Chapter 5 “The Passion of Ayn Rand”

I was very young when I first read Ayn Rand. First, I read The Fountainhead and then Atlas Shrugged. I did not know much about anything, but I was intrigued by the idea that commercial activity was not inherently evil like most pop culture was telling me.

I resonated with the ideas of competition, integrity, and holding to truth. However, I could sense there were other things that did not sit well with me even though I could not articulate them at the time. A deeper dive into her philosophy, objectivism, proves my young intuition correct.

Foster’s look into Rand, her books, and her philosophy captures this struggle. On the one hand, she is a defender of capitalism. On the other hand, you are not sure you want her on your side.

Objectivism

The two novels I mentioned above are fictional stories she wrote to illustrate objectivism.

Rand believed there was an “objective” world accessible to us all through the use of our minds. That is certainly what most people believe, at least implicitly, except that Rand and her followers seemed also to believe that the mind was a tabula rasa, a blank slate with no innate mental structure. By some unexplained process, however, this formless mass called “mind” could allegedly come to an “objective” understanding simply by thinking “rationally” about sensory output. (p. 118)

I know now that I disagree with the blank slate idea. Cognitive psychology research shows babies are born with lots of programming in place with an inborn sense of fairness in relationships as well as a language acquisition framework among other things.

Utopians likewise think we are born with a blank slate which is why they think if we can get the right society we can get good people. The Utopian philosophies and objectivism are materialist in nature, denying the existence of a spiritual realm and a creator God.

Rand was uncompromising in her philosophy. While she could identify the wrongs in society, she could not create a workable system to correct it.

…one of Objectivism’s fatal weaknesses: it offered no realistic political program for correcting the wrongs that it claimed to see because it refused to compromise, which not merely cut it off from mainstream politics but helped turn it into a closed cult. (p. 106)

It is less a philosophy that can be adopted and more a cult of personality. Foster notes this can be seen by looking at those who are a part of the Ayn Rand Institute today. He discusses a conference he went to that put on a documentary about Rand as well as conversations he had with members of the Institute.

They all refuse to talk about Nathaniel Branden, a man who once was in her inner circle who she had an open 14 year affair with. However, once he began another affair with a younger woman, he was essentially kicked out of the club and airbrushed from her history. (p. 109)

You could argue that a person’s private life should not be dug up to cast doubt on their public life, but in this case Foster observes she is not living up to her own standards.

The Branden affair, with its messy end, represented more than merely salacious detail; it fundamentally undermined Rand’s claims that man (and presumably woman) was a creature capable of controlling his emotions and acting “rationally.” (p. 110)

Rand’s philosophy glorified “rational selfishness.” (p. 102) One of the first lessons I try to teach in intro microeconomics is the difference between selfishness and self-interest.

We do not glorify selfishness because that is taking self-interest to the extreme where all you care about is yourself no matter the outcome to others.

You can act in a way that is self-interested, trying to choose the best option for yourself, while still taking in account how others are impacted.

Sadly, with her use of selfishness, she seems to mean self-interest as I describe it, but I guess she liked the shock value of using the word selfish, which just further hands ammunition to critics of capitalism. (p. 104)

She offered up selfishness as her moral defense of capitalism. From there, she concludes altruism is evil. This is another problem for supporters of capitalism! Please, stop helping us.

Here, though, some is lost in translation. She was apparently reacting to a view from a French philosopher named Auguste Comte who held an extreme view that the only moral acts are those that promote the happiness of others.

This definition of altruism is a denial of self that results in collectivism where everything we do is for the group.

That is what Rand detested. She believed in a radical individualism that is as far from Comte as you can get.

Now that altruism is more synonymous with generosity, her extreme statements against altruism do not play well.

You do see this idea in her novels. Like in Atlas Shrugged, many of her villainous characters are pretending to care about others, and they use that as a bludgeon against her heroes to prevent them from living their lives with complete truth.

For her, no one could be altruistic as defined by Comte so saying you value altruism is proof of your villainy.

We see this conflict about her stance on altruism in remarks from economist Jeffrey Sachs who has devoted his life to championing foreign aid to poor countries.

Sachs said she was an “awful woman” who preached “ antagonism to compassion.” (p. 104)

This could be an example of what Rand is talking about: the givers feel altruistic and noble even though many cases of harm from such charity can be demonstrated because of the violation of radical individualism. Aything that increased man’s dependence on another man was evil to her. (p. 105)

Conclusion

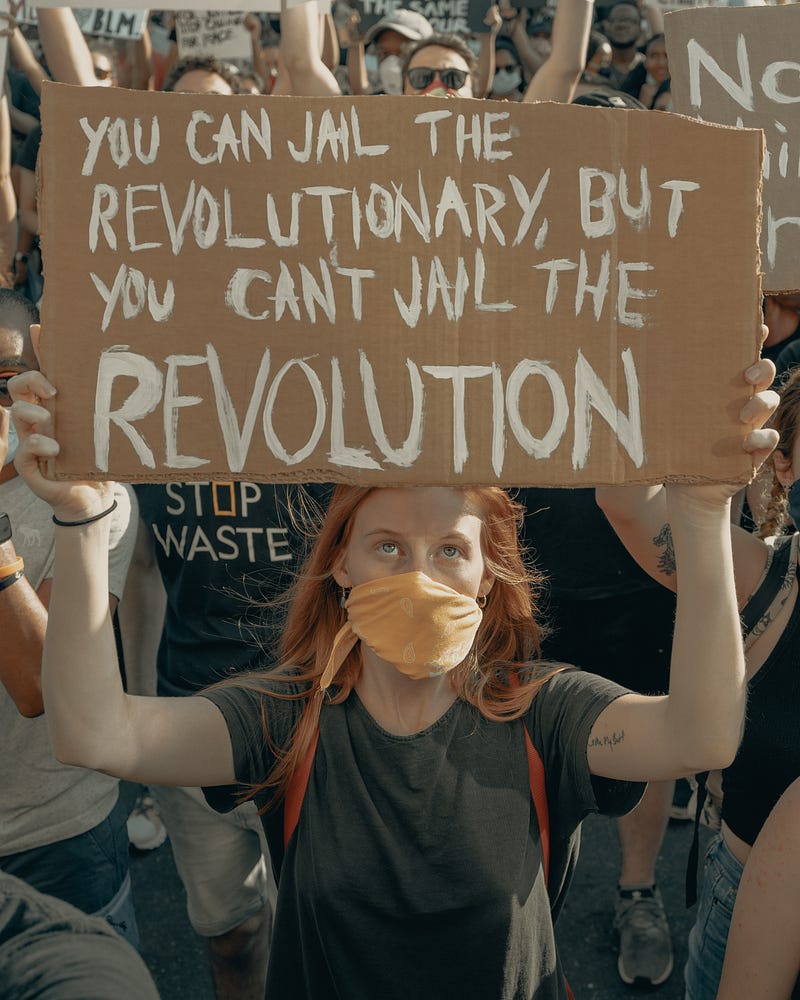

Rand was naturally criticized by the Left. Her radical individualism is in complete contrast to their various collectivist views.

And yet Rand often criticized prominent figures on the Right, specifically those who champion the free market who would be considered Rand supporters.

She called Friedrich Hayek a “pernicious enemy” because in her eyes he compromised with collectivism. (p. 112) Hayek wrote “A Road to Serfdom” which many on the Right embrace as an anthem against big government.

She also attacked Milton Friedman and George Stigler for their arguments against rent control. She agreed rent control was bad but thought the basis of their arguments were “collectivist propaganda” because they did not argue for the “inalienable right of landlords.” (p 112)

Rand is essentially an island, not on the Left for sure — she vehemently disagreed with collectivism — but not happy with those on the Right. You had to agree with her completely.

We can get some more understanding of her dogmatic adherence to objectivism if we look at her early years in Russia during the Russian Revolution, which we will do in the next blog.

Reference: Foster, Peter, 2014. “The Passion of Ayn Rand” Chapter 5 of Why We Bite the Invisible Hand, Pleasaunce Press.