A Discussion of Bourgeois Equality Chapter 62 “After 1848 the Clerisy Converted to Antibetterment”

As we start Part X, the last part of Dr. McCloskey’s book, she turns to the threats facing the Great Enrichment.

She has argued that what allowed the Great Enrichment to take root in England around 1800 was at its root a change in ideas and rhetoric that accepted and valued the dignity of the common man.

Now in this chapter she notes there was an attitude change in the clerisy in 1848. She does not explain at this point the significance of 1848, but I suspect it may be due to the publication of Karl Marx’s “Communist Manifesto” that February.

She notes anti-capitalist views took root for various reasons including the advent of photography in the early 1900s that allowed people to see the dark side of early industrialization like the Lewis Hine photo of the little girl working in a cotton mill. (p. 595)

She also notes that the children of Protestant ministers grew up to join the progressive Social Gospel movement, which McCloskey calls “diverted Christianity.” Over time those in this movement became more interested in material progress than spiritual progress.

Finally, but not least, there was a rising feeling that we could engineer a better way through policies, which saw the rise of the utopian movement as well.

And a new prestige for social science and the making of statistical surveys led to the conviction that people could be engineered, with results that would be better than profit-driven trade. (p. 595)

But how could these ideas have taken over if the Great Enrichment is responsible for such dramatic increases in our standard of living? How could we turn to ideas that would undo its great success?

Largely the reason is because the resulting income rise took years to be recognized.

But anticapitalism came in part also because trade-testing disturbed the society without at first enriching ordinary people greatly. It did enrich them eventually, and spectacularly, but too late in the nineteenth century to scotch the feeling in the clerisy that laissez-faire individualism in politics had failed. (p. 595)

In fact, McCloskey notes that the social disruption led to the rise of various movements to counter the problems including trade unions, socialism, and progressivism. When the rise in real wages finally arrived due to the trade tested system of betterment, it was perceived by many to actually be due to these other institutions. (p. (595)

She quotes historian Mike Rapport about this mistake.

“With more forbearance in 1848…the liberal order [on the Continent] would have survived, and within a generation…[Continental] Europeans would have enjoyed both constitutional government and the wealth created by maturing industrial economies.” (p. 595)

But sadly that did not happen and McCloskey shows the shift in the clerisy’s attitude by looking at art, books, and the like.

Painting in seventeenth-century Holland, by contrast, I have noted, celebrated bourgeois virtue, a celebration that cannot be found much by the time of Picasso and Diego Rivera — though consider Norman Rockwell, despised by the elite of the clerisy. (p. 591)

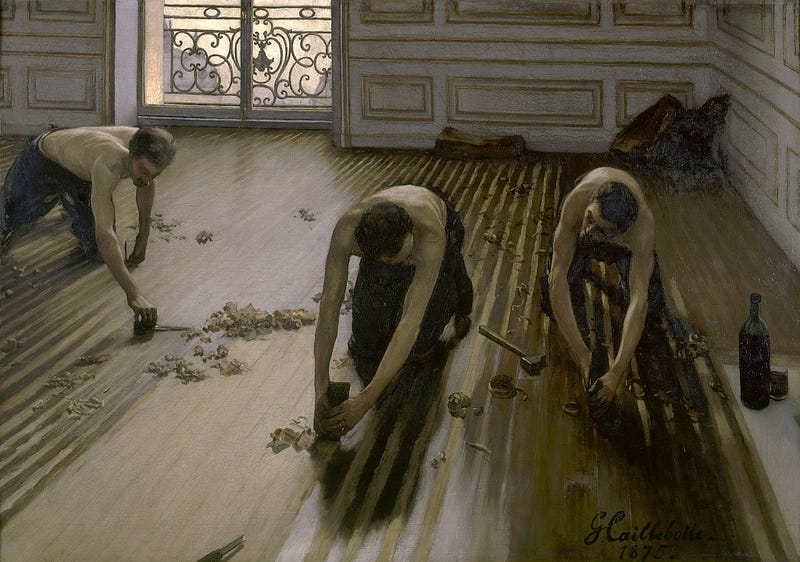

McCloskey notes an unusual work for its time, Gustave Caillebotte’s “The Floor Planers”, pictured above, shown at an Impressionist exhibition in 1876. Most painting at this time did not feature people working, in contrast to the Dutch paintings of the 1600’s that did celebrate the bourgeois. (p. 591)

McCloskey quotes Emile Zola, a supporter of impressionism in general, as saying of “The Floor Planers,” that a “painting so accurate…makes it bourgeois.” (p. 590) And McCloskey notes that was not meant as a compliment.

Zola did later give praise to Caillebotte when he painted “Street of Paris by Rainy Weather” that showed the bourgeois at leisure, not at work.

The tragedy is that just as the fruits of the Great Enrichment were being realized, there is a Great Conversion around 1848 when the intelligentsia turn against it, threatening its continued existence. She explores this further in the next chapter.

Reference: McCloskey, Deirdre Nansen, 2016. “After 1848 the Clerisy Converted to Antibetterment,” Chapter 62 of Bourgeois Equality, The University of Chicago Press.