Part 1 of a Discussion of Peter Foster’s Why We Bite the Invisible Hand Chapter 6 “Tuesdays with Mandeville”

Foster is tracing anti-capitalist thought across many writers of the West, and in this chapter he hits one I had not heard of: Bernard Mandeville who was born in 1670 in the Netherlands and became a doctor and a writer living in London.

I have previously commented on Dierdre McCloskey’s Bourgeois Equality in which she traced the origin of tolerance for bourgeois virtues that allowed capitalism to take hold eventually in England.

The ideas first coalesced with some success in the Netherlands though.

Ultimately, the bourgeois who first enjoyed success preferred closing the door behind them instead of allowing capitalism to bloom and flourish, which is how England ended up being the birthplace of capitalism some decades later.

Prior to that time, England, like the rest of Europe, had a medieval mindset which was largely hostile to merchants and trade.

Back to Foster’s book, Mandeville put in writing many of the anti-capitalist thoughts that still live today. (p. 125)

Anti-commerce may be more appropriate since capitalism as we know it would not kick off for more than 100 years after he was born.

With knowledge of Mandeville’s thinking, we get a better understanding of Adam Smith’s book, Theory of Moral Sentiments, in which he started off with the intention of refuting Mandeville.

But, I will dive more into Mandeville and Smith in the next blog. Here, I will focus on Foster’s comments on other anti-capitalist sources, in particular the poet William Wordsworth and the popular novel, Tuesdays with Morrie.

Wordsworth and Morrie

Foster notes that Wordsworth “was a leading light of the Romantic movement.” (p. 122)

The Age of Enlightenment with its strong emphasis on reason that ran from the late 1600s to the early 1800s spurred Romanticism, which ran from the 1700s to the mid-1800s, as a reaction.

With its emphasis on nature, imagination, transcendence, and beauty, Romanticism looked aghast at the ugliness of early industrialization.

Foster observes that Wordsworth served as a

…representative of sensitive aversion to the conspicuous squalor and hardship of the nascent factory system and to commercial society’s allegedly relentless “getting and spending.” (p. 122)

We can see this in a famous poem of his, “The World is Too Much with Us,” excerpted below.

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

The Enlightenment thinkers differed some amongst each other, and they are often grouped geographically into schools of thought. Overall, they agreed on a strong emphasis on rational thinking and progress through debate. David Hume and Adam Smith were two big figures of the Scottish Enlightenment. (p. 122)

Neither was Wordsworth a fan of Scottish Enlightenment philosophers. He called Smith “the worst critic, David Hume excepted, that Scotland, a soil to which this sort of weed seems natural, has produced.” (p. 122)

The anti-modern world, anti-man made, anti-reality, sneering quality of Wordsworth and the Romantics continues to pop up in culture today. Foster uses the phenomenon of Tuesdays with Morrie to illustrate an example.

I was in grad school when it exploded into pop culture so even though I never read it, I have heard of it. I will rely on Foster’s take on it.

Apparently the author, Mitch Albom, got back in touch with his professor mentor, Morrie Schwartz as he was in his last months, dying from ALS.

They began meeting weekly on Tuesdays as they had in the past.

Tuesdays is a reputedly heartwarming story set during the final months of a former university professor, Morrie Schwartz. At a series of Tuesday meetings, the professor passes on pearls of wisdom to Albom, a former pupil and now a star sports reporter and broadcaster. (p. 133)

Foster is not impressed with this book at all, despite how pop culture went crazy for it in the late 1990s. He first dislikes how disingenuous it is in its presentation.

Foster says Albom writes that he decided to record their sessions starting with the third one just to be able to remember Morrie’s wisdom, as opposed to it being a part of a plan to write a book. I suppose that sounds more heartwarming.

And yet, Foster notes that Albom eventually revealed the book was Morrie’s idea and both of them were sharing the advance for the book. (p. 134).

Foster mentions this because it casts a different light on the character that Morrie presents because of the observer effect, where the act of observing influences what is being observed. Morrie was not just speaking to Albom but to all the future readers.

Not that Foster is all that impressed with Morrie’s wisdom, rather, he is quite critical.

The much bigger problem was that Morrie’s philosophy ranked in profundity with that of Hallmark Cards. Indeed, at times the greatest threat to his life appeared that he might drown in his own cliches. (p. 134)

Meow!

So if Morrie is not actually profound, what was it in this book that resonated with the popular audience?

Sneering at American capitalist culture. (p. 134)

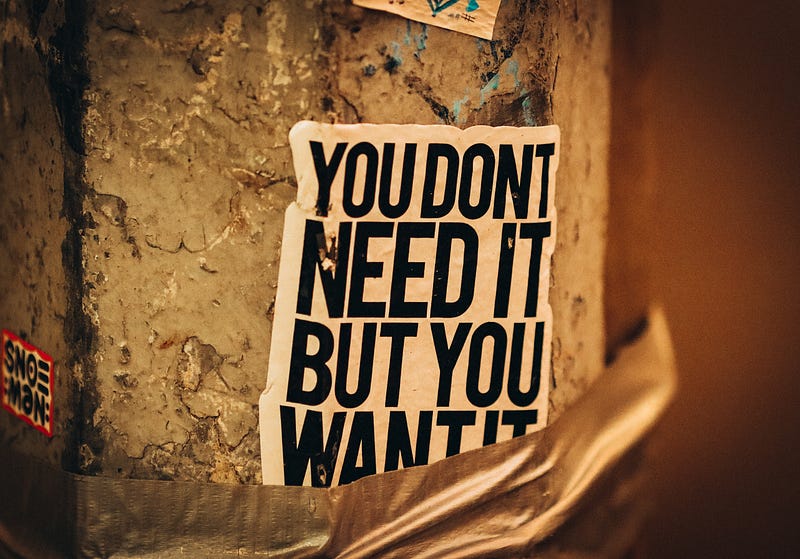

Morrie noted people confuse their wants with needs. People do not need to buy the latest TV or sports car or a bigger house. (p. 135) He, in contrast, has kept his old TV and car and has not fallen for this trap.

But wasn’t it worth reflecting that Morrie actually had a TV and a car and a house? And who, exactly, was meant to mandate the acceptable level of automobile features or square footage that people “need”?…He had splashed out on lots of medical equipment that he wouldn’t have been able to afford without the book advance, and that wouldn’t have been available outside a rich, technologically advanced “materialist” society (and don’t forget that tape recorder.) (p. 135)

And that is the way it goes with most critics of capitalism. There is a complete lack of understanding or realization that the great wealth they take for granted is only in existence because of capitalism. No other system has achieved anything more than subsistence for the general population.

Even the Scandinavian countries people point to as examples of successful socialism actually consider themselves capitalist. They have an extensive welfare system to redistribute wealth, but they have the wealth to redistribute because of capitalism.

In another chapter, Morrie told a story of how he had almost ended up working in a sweatshop. Morrie swore he would never work somewhere that “exploited someone else” or that he would “make money off the sweat of others.” (p. 136)

This is the typical fixed pie thinking of a Malthusian where one person’s gain is another person’s loss.

Entrepreneurs are not exploiting people; they are using their visionary gift to pull together all the resources needed to create a business that provides jobs. And people voluntarily working for a paycheck are not exploited. It is mutual gain.

And just because it is a job you do not like, or consider beneath you, does not mean all else will feel that way. Morrie notes he escaped this world of exploitation by heading to academic research, “where he could contribute without exploiting others.” (p. 136)

Really? As Foster notes, where do you think the university gets the money for its endowment? And where do people get the money they use to pay tuition? (p. 136)

And should we all do academic research to avoid this exploitation? I would like to hear how that economy is supposed to work!

Morrie subscribed to the stock Rousseauian nature-versus-nurture view that we are all corrupted by a society that has somehow emerged despite us, or has been inflicted upon us. (p. 137)

What is interesting about the “Tuesdays with Morrie” book is how popular it was. Why are so many of us so happy to read about how bad capitalism is while we all benefit from it greatly? What kind of hypocrisy is this?

The writings of Bernard Mandeville first explored these issues of hypocrisy around commerce that we will dive into in the next blog.

Reference: Foster, Peter, 2014. “Tuesdays with Morrie” Chapter 6 of Why We Bite the Invisible Hand, Pleasaunce Press.