A Discussion of “The Historical Production (and Consumption) of Unsustainability”

My last couple of stories have examined the unsustainability of our diet,

…and an escape from the unsustainability of our agricultural practices.

Today, I want to examine unsustainability itself. I turn to an article published in The Hedgehog Review, an interdisciplinary academic journal focused on contemporary culture.

I must confess it is strange as an economist to read an article with no equations or statistics!

But the idea of sustainability is key, not only in the issues around diet and agriculture as covered above but also in many of my students’ questions:

- How much debt can the US government add?

- How long until the US dollar collapses?

- Will Bitcoin or other digital currency continue to rise?

There is no definitive answer to these types of questions except for Stein’s Law:

A bit glib but really the only answer. When you are in the middle of an unsustainable activity, you know it will end but not when. And inertia alone will keep things moving along until it no longer can.

Basic Idea

Cohen (2012) examines the unsustainability built into our technology, policy and culture.

He observes that it is the creation of industrial production more than 200 years ago that has created the seemingly unsustainable world we live in today.

It was not a thought out, carefully constructed plan by an evil cabal. Instead as one development led to a problem, we lurched to an apparent solution that only later we realized caused more problems.

The Industrial Revolution was the miraculous start. Mankind had persisted for centuries with little to no economic growth, meaning most people lived near the subsistence level, often slipping below it.

What the Industrial Revolution created was a world where the limited resources we had could be used to produce a much higher standard of living for more than those at the top. But did it do so in a way that was sustainable?

Cohen points out 3 ways our system has developed without an eye to sustainability.

Maximizing Profits

The goal becomes profit maximization so things must be measured and controlled.

To the extent something increases profits it matters. Issues that do not hurt profits are ignored.

That means externalities — any cost or benefit that comes from the production of a good that the producer does not absorb. Pollution is the most common negative externality.

If a manufacturer has wastes created that he can dump into the air or water, there is no impact on his profits. And if profits are the focus then that is a sensible decision. Obviously, this causes costs to others who rely on the air or water.

This is one way that the miracle of the Industrial Revolution came with unsustainability.

Sourcing the Inputs

In order to produce in an industrial system, thinking gets reduced to inputs and outputs.

In a sustainable system, the inputs come from within the system like in regenerative agriculture which is a set of practices focused on creating and renewing the soil.

While the output consists of crops, meat, eggs, etc., many of the inputs are regenerated in the system. The literal wastes of the animals becomes an input to the soil to grow the crops. The weeds and insects that are a byproduct of growing the crops become inputs to the animals.

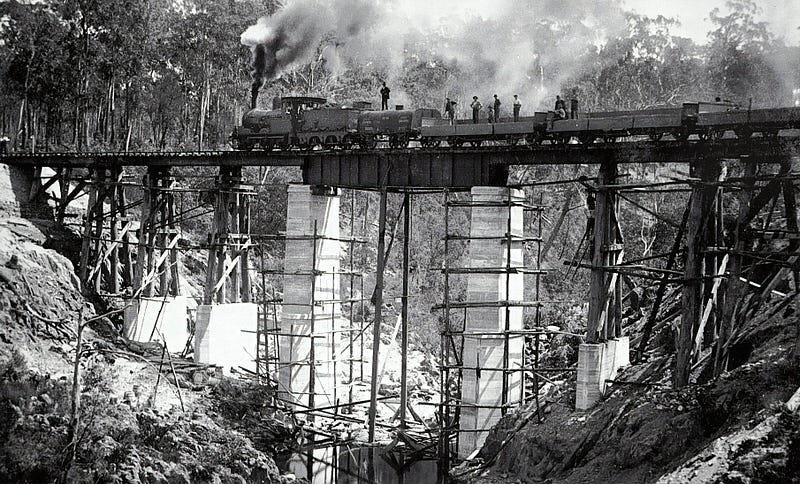

Contrast this to a system that relies on inputs from the outside. Cohen uses a train as an example.

Trains need not be hampered by rainy weather, hot or cold days, dark nights, icy passages, or muddy roads. Nor need they rely on the organic limits of animals that have to be fed, rested, and paced. At the same time locomotives draw from fuel inputs (coal or wood) outside the system, requiring constant extraction and dependence on mined resources. (p. 42)

This is not to condemn technological improvements. It is to point out that as our technology improved, sustainability was not incentivized.

With trains, outside fuel is potentially a constraint but not one worth considering when there were abundant resources. It is only later as the system was built up that it can begin to feel like an unsustainable constraint.

Incentivizing Consumption

Prior to the boom in mass production, people largely consumed what they produced. Consumption as we think of it today was not a dominant force.

But with such a large increase in production, we needed consumers to consume! Thus, Cohen argues, a consumerist paradigm is needed.

By the first half of the twentieth century, that culture of production was secure enough to provide the foundation for other developments. In turn, the twentieth century fostered a culture of consumption…having mastered the principles of mass production, it was time to invent mass consumption. (p. 45)

Today many consumers are overweight from too much consumption of food and in debt over too much consumption of everything else.

Results

With Cohen’s analysis we can see that we now live in a world based around unsustainable consumption with entrenched interests who do not want to produce less or have less consumed.

But, we did not get here because of a diabolical plan of the shadowy elites. Our “today” does not come from a planned outcome. Instead we have landed here somewhat accidentally.

The technological breakthroughs of the Industrial Revolution made it possible to increase the standard of living for billions of people in the past 200 years. It is difficult today to think of a world where abundance was only a dream. The people of that day were sure that anything that increased output could only be good.

They could not see the unsustainable world they were building as Cohen notes.

It took concerted efforts to build the infrastructure into our cultural and environmental landscapes that is now difficult to sustain, an infrastructure of modernity that draws from nature’s resources, distances humans from the land, operates without a sense of limits, and follows from a reduction of ecological realities…to anthropocentric constructs. This coterie of distance, limitlessness, extraction, and anthropocentrism adds up to produce a world always outpacing our capacity to keep something going. (p. 38)

Conclusion

I do not subscribe to the negative Malthusian thinking of much of the environmental movement. Thomas Malthus wrote in 1798 about his fears of overpopulation primarily based on his belief that population would grow exponentially and food resources would grow linearly.

He did not realize the growing ability of the industrial revolution developing around him that was really going to do the opposite: create abundant food while population would relatively slow its growth.

However, I do think that we could, and should, decide to add sustainability as a value to our system rather than waiting for Stein’s Law to kick in and force our hand.

Our obesity epidemic could be looked at as an unsustainable limit to consumption. What started as a desire to produce enough food to end famines has led to policies incentivizing an unhealthy, grain-based diet where you have companies like soda makers fighting for our “stomach share.” (p. 48)

As an economist, I know profit maximization and the price signal are key to guiding business behavior. Just telling a business to be sustainable is not going to work if it is not tied into the profit motive.

We could instead focus on our culture. Change the original consumption paradigm that focused on consumers consuming all that is produced to a new consumption movement focused on valuing sustainable products. Businesses follow changes in consumer demand.

We can change our farm bill policies towards regenerative agriculture and away from cheap, unhealthy, unsustainable grains. Our current policies result in the unhealthiest food being the cheapest.

We can examine the tax code and provide tax credits and deductions that incentivize sustainable business practices.

We can either choose to make decisions like these that will move us towards sustainability or we can wait until things stop and deal with the consequences.

After all, if something cannot go on forever, it will stop.

Reference: Cohen, B. 2012, “The Historical Production (and Consumption) of Unsustainability: Technology, Policy and Culture.” The Hedgehog Review, Summer 2012, 37–51.