A Discussion of Bourgeois Equality Chapter 56 “The Change in Ideas Contradicts Many Ideas from the Political Middle, 1890–1980”

Not only is this chapter starting Part 9 out of 10 of Dr. McCloskey’s book, but these last 2 parts are addressing the fourth, and last, big question: What are the dangers?

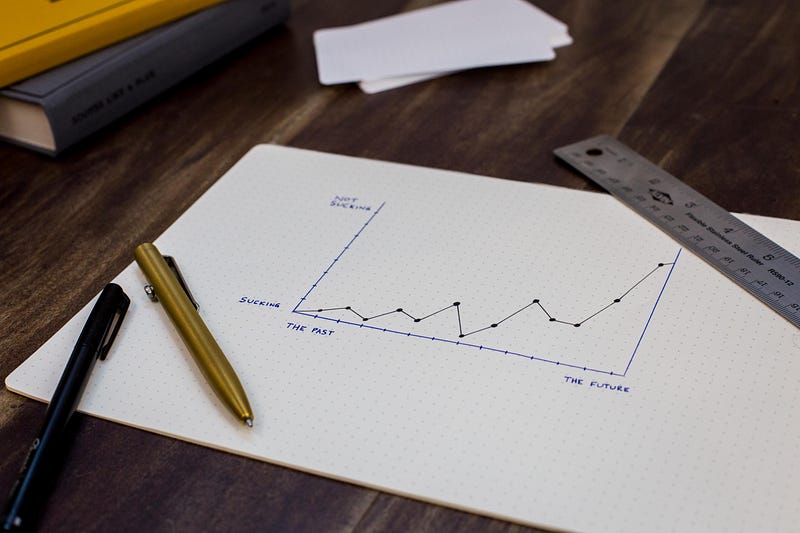

That is, what are the dangers to the Great Enrichment process that has magnified economic growth not 2 or 3 times but over a 100 times?

She starts with a simple restatement of the book’s thesis.

The rhetorical and ethical change around 1700, I say,…caused modern economic growth, which at length freed us from ancient poverty. (p. 531)

And then she introduces a new idea for this section of the book.

Modern economic growth did not corrupt our souls, contrary to the antibourgeois rhetoric of the modern clerisy since 1848, and contrary also to an older line of aristocratic and priestly sneering at bourgeois life. (p. 531)

Here she is noting two major groups who are against the rising bourgeois of the Great Enrichment.

- The modern intellectuals who resent the merchant class who earn more money than they without earning all the fancy degrees.

- Those who feel more of a claim to the upper class by pedigree or family money and look down on the monetarily successful bourgeois.

Those enemies of the Great Enrichment she will return to throughout the rest of the book.

For now she is focusing more on how economic historians and others are not attributing the Great Enrichment to the right source: the change in rhetoric that attributes dignity to the bourgeois merchant and inventor.

She asserts that the Industrial Revolution and the Great Enrichment are conflated incorrectly. Industrialization did contribute to accelerating growth in the eighteenth century, but there had been other times and places of industrialization that did not go on into the Great Enrichment.

For example, the late Tang dynasty in China around 800–900 AD experienced many of the features of industrialization including growing investments and cities. Yet the Great Enrichment did not start there. (p. 533)

Nor does she agree with other economic historians that the Great Enrichment was a continuation of the growth process that started in the medieval era and just gained steam. She calls those who ascribe to the this idea, the Continuists.

She notes industrialization can explain a doubling or tripling of growth but not the growth we saw with the Great Enrichment of 10, 30 or 100 times. (p. 535)

It was not just industrialization, but a shift in ideas, first from the Dutch, that then migrated to England.

The roots, however, would have shriveled, as they so often had for earlier industrial revolutions, if they had not been accompanied this one time by a dramatic change in ideology. The British enrichment — out of Holland — came above all from a change in ideology. The British bourgeois-admiring ideology. (p. 536)

It’s not just wealth that has grown with the Bourgeois Deal of the Great Enrichment. The system encourages ethics and harmony.

Lives spent trying to figure out what customers want and how to get the item to them in a nonruinous way and how to improve service and quality at a lower cost, one could argue, lead the bourgeoisie to ethical attitudes superior in some ways to those of a haughty aristocrat or an envious peasantry or a proud clerisy. (p. 539)

She tells the tale of one trade tested betterment that led to refrigerated train cars. (p. 539) Gustavus Franklin Swift figured out how to ship meat in refrigerated train cars rather than shipping live cattle from Chicago to the East in 1880.

The problem is trains would make more money with the live cattle method so they were not wanting to adopt this new betterment. If it were today, the railways would likely have appealed to the government to protect jobs or public safety to stop this betterment. (p. 539)

Swift found a smaller railway to get his refrigerated meat cars to ship from Chicago to Detroit and then went through Canada to get to Boston, bypassing any attempts to appeal to Congress. His competitor copied him.

The result? Cheaper prices for meat in Boston by the success of this trade tested betterment. Swift and his competitors profited, too, of course, and then they went on to fund various charitable activities. All were helped. (p. 540)

This trade-tested system of betterment rewarded the bourgeois who figured out better ways to do things and ultimately that was what allowed the standard of living to rise for all. The Great Enrichment was a time when they were allowed to put these ideas into operation, unlike all the other times in history when government, aristocrats, or religions put a stop to it.

But that should also show us how delicate the Great Enrichment is. A lack of respect or understanding of it as the source of our growth could lead to a loss of it.

People in the poorest countries nowadays, who assume not unreasonably that their economies are zero-sum, reckon that they can best advance by theft, graft, influence, corruption, rent-seeking. People in rich countries reckon, on the contrary, that the best way to advance is invention and betterment, which is why such countries became wealthy, at any rate until government expenditures got large enough to encourage rent-seeking to take over again. (p. 535)

Reference: McCloskey, Deirdre Nansen, 2016. “The Change in Ideas Contradicts Many Ideas from the Political Middle, 1890–1980,” Chapter 56 of Bourgeois Equality, The University of Chicago Press.