A Discussion of “Financing Higher Education in an Imperfect World

Pssstt! I got a secret.

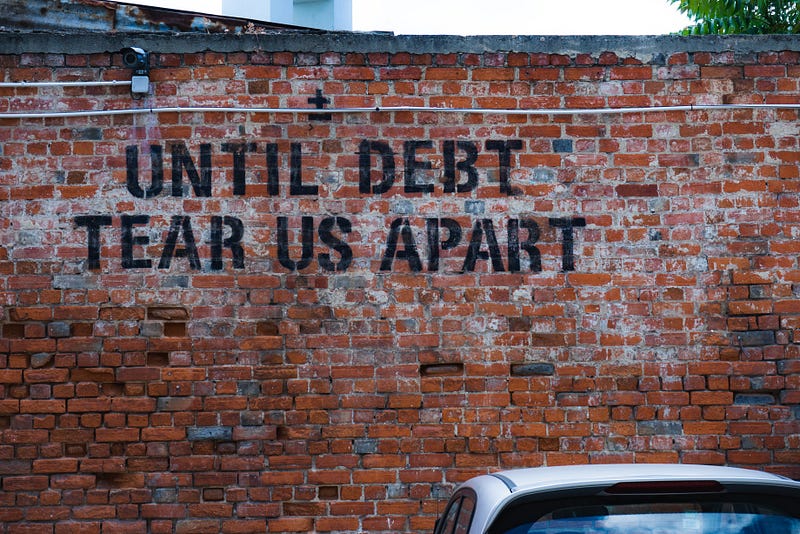

College debt is soaring.

OK, not really a secret. Search Medium and you can find article after article decrying the situation. But what can we do to fix it?

That is what Long (2019) is investigating in his article about Income Contingent Loans (ICL).

What are ICLs?

Details can vary but in general, ICLs are

schemes whereby the amounts the individuals are required to repay in any period is dependent on their income in that period. (p. 23)

There is not a fixed dollar amount that must be paid back each period — instead you owe a percentage of your income. Currently, students typically pay back a fixed monthly regardless of their situation. And the monthly amount is higher as the amount borrowed increases.

Should Government Get Out of Education?

College did not used to be this expensive. Unfortunately, a side effect of government efforts to subsidize college and encourage more to attend is the increased price.

In a nutshell, any time a subsidy is given, the result is more people buying the product. And the result of more demand is higher prices. The subsidy offsets that some, but not completely. Were we better off before government got involved?

I personally love Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand analogy — each person pursuing their own self interest will actually find themselves serving the needs of others.

That is, if you want to make money to buy the things you want, you have to fulfill duties as an employee thus providing a good or service, open a business as an entrepreneur thus providing a good or service, or even innovate and invent thus providing a new good or service.

And your efforts will only succeed if you are providing a good or service that people want.

That is the magic of the invisible hand. You want “stuff” and the only way to afford the stuff is to do things for others. Beautiful.

However, economists know this story only works under certain conditions — failure of meeting these conditions may mean the Invisible Hand cannot function optimally. As Long (2019) details, (p. 24)

- Firms cannot use market power against consumers

- No rent seeking groups, which means special interests that can lobby for special rules or favors.

- A perfect insurance market exists, which means there is affordable, actuarially fair insurance

- A perfect credit market exists, which means you can get a loan today based on your future income

Under those assumptions, just leave it to the market!

In the real world, we deal with the issues in #1 and 2 with anti-trust legislation and anti-corruption laws.

The problems of #3 and 4 are relevant to the financing of higher education.

Market loving people could say government should stay out of higher education, but that ignores that #3 and 4 require perfect information.

Instead, we face asymmetric information, an example of a market failure.

With asymmetric information, one party in the transaction knows more than the other. In the presence of asymmetric information, it is reasonable to expect that the credit market for college loans is not complete and perfect.

Arguments for Government Involvement

As a result, Long argues government should be involved in financing college education. Specifically, asymmetric information causes 2 problems, moral hazard and adverse selection.

- Moral Hazard: “a fully insured individual would not have an incentive to make the required effort to reduce risks, if effort levels are not verifiable.” (p. 24)

Imagine you have a tree hanging over your house. If it falls, you will expect your homeowners policy to cover it. If they can prove you knew it was dead and did nothing about it, they can deny it.

Result? The more unlikely it is that they can prove your negligence, the more unlikely it is you will spend the money to cut down the tree since you are fully insured.

Applying moral hazard to borrowing for college with an ICL, you may choose a lower income, higher leisure occupation than you would have under other repayment plans.

- Adverse selection: “individuals misrepresent themselves to take advantage of contractual arrangements intended for others.” (p. 24)

One example could be unemployment insurance. It is intended to help people who find themselves unemployed for a time until they can find a new job.

Someone who is able to line up a job quickly is not a member of the group this is intended for. But someone who can secure a job and delay starting it for 2 months, collecting unemployment in the mean time, is misrepresenting themselves.

Applying adverse selection to borrowing for college with an ICL, you may know you are not going to work once your finish college, or in some other way know your income will be lower, and thus you know you will potentially not be fully repaying your debt under the ICL.

And all that means is there will be fewer college loans made and the interest rate charged will be higher.

Thus, Long justifies a role for the government to administer the ICL program because the reason

…these risks should be shared by the government rather (than) by (the) private investors is that the moral hazard and adverse selection problems can be more efficiently mitigated by the government, thanks to its superior ability to collect information about individual’s income. The market system, by itself, would not provide efficient ICL schemes, because of high informational and enforcement costs that private lenders face. (p. 23)

Modeling

The rest of the paper is building a model of an ICL program to show the most efficient outcome is when the borrowers pay a percentage of their income rather than a fixed monthly payment.

That is,

…the individual is better off if her debt repayment is permitted to be low in periods when here earning is low, even if she is required to pay off her debt in full. (p. 28)

If you want the ICL to be designed so people are not required to pay the debt back in full if their income is lower than expected, that will raise the payments of the others if the scheme is to break even. A program that breaks even would be a much easier political sale to those who are fiscally conservative.

But as Long points out, this is the essence of social insurance, “those luckier than average will end up paying more than the average person does.” (p. 28)

With this in mind, Long goes a step further to suggest an ICL model that is not a simple linear percentage of income but instead is “a piece-wise linear one”. (p. 28) The lower repayments from those with lower income will be offset by higher repayments from those with higher income, thus allowing the program to break even.

The ICL becomes a form of social insurance. To the extent we do not know our future income or luck when we start college, it makes sense to belong to a social insurance scheme that will help out those with the worse outcomes by having those with the best outcome chip in more.

While you have some ability to increase the likelihood of having high income by choosing a major that pays better, you cannot predict any negative health shocks, for instance, that could befall anyone.

Long uses his model to show that the most efficient outcome is where the percentage of your income you must pay back is higher if your income is above a certain amount, which will allow those with lower incomes pay back a lower percentage.

Conclusion

If you made it this far, congratulations!

The power of this article for someone who wants to change the college loan market is it has intellectual power. It is not just saying the current system is unfair. It is giving reasoned argument and mathematical evidence for a solution.

It is an interesting proposal of individualism and community values. That is, it is the individual who is taking out the loan in an attempt to increase their incomes in the future by increasing their human capital.

While the individuals benefit directly from this effort, all of society benefits as well. As economists say, there is a positive externality for everyone as incomes rise and thus tax revenues.

Thus, the positive externality, along with the asymmetric information problems, create market failure and thus a role for government to administer the ICL scheme, not the private sector.

In addition, no one really knows if they will be in the lower than average income group or the higher than average income group. Their lack of knowledge of their future income combined with those external shocks of good or bad luck that no one can predict, suggests making a pact is favorable for all.

Long only considered 2 brackets, above average and below. It is easy to imagine there being 3, 4 or 5 levels where the percent you pay back increases as your income increases.

In this way, a scheme could be created that does not cost the taxpayer but instead redistributes the gains from higher education. Those who succeed will pay a higher percentage of their income than those who earn less than average income, but since you cannot know which group you will be in, it is still a good deal to make.

References:

Long, Ngo Van (2019). “Financing Higher Education in an Imperfect World.” Economics of Education Review, 71: 23–31.