A Discussion of “A Dialogue between a Populist and an Economist”

In an unusually playful academic article, Boeri, Mishra, et al. (2018) write a script of two people, Populist and Economist, arguing over the success (or failure) of economics in explaining the latest wave of populism fever that has spread to many countries around the globe.

The populist is criticizing the economist for focusing too much on economics and missing the true picture.

The economist concedes the field’s first theories focused on “the political economy cycle” evidenced by the incumbent winning if the aggregate economy was good. (p. 191) This would incentivize politicians to run expansionary monetary and fiscal policies ahead of an election to help their victory.

The data is supportive of that theory so it seems natural enough for economists then to hypothesize that negative economic shocks could give rise to populist leaders as the people look to change the system.

However, here the data is not so supportive. The populist gives examples that violate that hypothesis. (p. 191)

- Populists are in power in Poland but there was no economic crisis there in the last 10 years.

- Ireland and Portugal did have deep negative economic shocks but there is no populist party.

- Switzerland, too, has had a strong economy but also strong populist parties.

To explain this, our populist turns to the definition of populism,

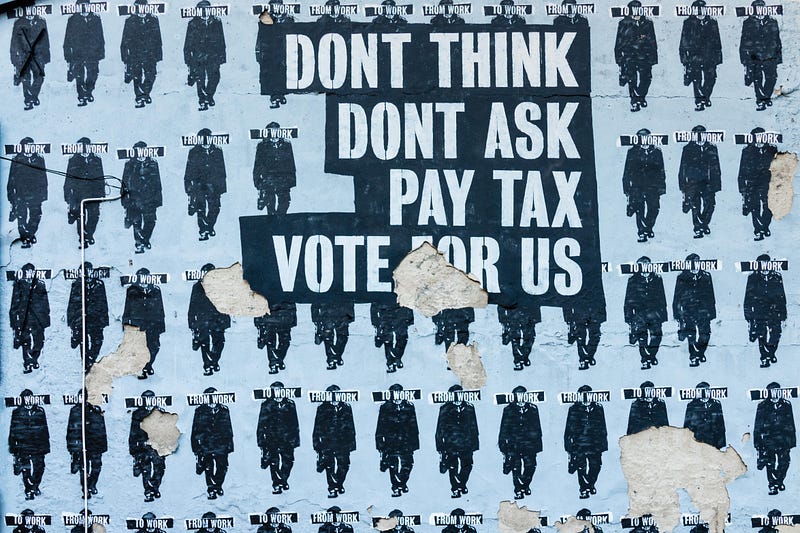

…a thin-centered ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic camps, ‘the pure people’ and ‘the corrupt elite’ and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale of the people. (p. 192)

That is, an element of populism is how people feel about the elites and how they are running the important political institutions.

Thus, the populist brings in a non-economic factor: the degree of trust voters have in the institutions of their country. By institutions, the article seems to mean political parties and the overall government.

The first hypothesis tested is, do negative economic shocks predict a rising vote for populists when there is a pre-existing low level of trust towards institutions? (p. 193)

To answer that, the economist turns to a cross-country plot between economic shocks and the share of votes for populist candidates.

On the horizontal axis is the change in the unemployment rate from 2004 to 2014 so if it went up, then that is a sign of a negative economic shock.

On the vertical axis is the average percentage of votes that went to populists.

Then data for European countries is sorted into high trust and low trust groups. For the high trust group, the trend line is horizontal — absolutely no relationship between votes for populists and the unemployment rate. In fact, the share of votes for populist candidates for all 7 high trust countries was 20% or less.

For the low trust group, there was an upward tilt to the trend line demonstrating that as unemployment rose, the average populist vote rose.

So interesting, but as the populist points out, it is more complicated than just one economic factor.

The economist is ever-ready for a more complicated regression to account for more factors to explain the share of votes for a populist party including (p. 194)

- Income — survey data showing which individuals in the data set consider themselves income sufficient or income difficult;

- Gender;

- Age — separated into 3 groups, under 30, over 65, and thus the group in between;

- Union — to capture individuals who belong to a union.

The idea is to include variables like this that might explain populist voting behavior beyond economic shocks or trust in institutions. It is always possible that the simple analysis described above is obscuring some other reason that relationship appears.

Results?

Interesting. But somewhat weak.

Once controlling for the above listed factors, the authors focus on two variables that allow them to investigate the impact of trust and economic shocks on the share of votes for populists.

They find that responsiveness of the populist vote to economic shocks for low trust countries is only statistically significant after the Great Recession (Post-2012) and not for Pre-2010 or the whole data set (2004–2014). Thus, they conclude,

“…in countries with a low level of trust, a higher unemployment rate is associated with a greater likelihood of votes for populist parties.” (p. 194)

They also find that in countries where trust in institutions is increasing, voters do not vote for populist parties even during times of economics shocks.

Thus, if establishment politicians want to save themselves from a populist wave, they need to build up trust in the political institutions. Without that, they are vulnerable to being tossed out when the next negative economic shock hits.

To some extent, that is what I discussed in another article that argued economic populism could be a necessary step in righting the system to prevent a more damaging bout of political populism.

Not surprisingly, the authors wrap up with a conclusion that is warming to the heart of the academics this is written for — evidence of more work is needed by economists into this area of political science!

Specifically, the authors mention looking into nativism (anti-immigrant sentiments) and the rural-urban divide as other factors that could play a role in the populist vote.

References: Boeri, Tito, Prachi Mishra, Chris Papageorgiou, and Antonio Spilimbergo (2018). “A Dialogue between a Populist and an Economist.” AEA Papers and Proceedings, 108: 191–195.