Part 1 of a Discussion of Peter Foster’s Why We Bite the Invisible Hand Chapter 8 “Do-It-Yourself Economics”

Foster dives deep into the assumptions he says we carry around unknowingly that cause us to make erroneous judgements about business and economics.

He cites work by Steven Pinker in the field of conceptual semantics, which examines the language we use to reveal what assumptions we are making about the how the world works. (p. 158)

Apparently, our language shows our intellectual discomfort with business. (p. 157)

- The common analogy of competition as “the law of the jungle”

- Journalists describing businesses as “battling for” or “stealing” market share

- Speculators “make a killing”

- Employees are “sacrificed to the bottom line”

Metaphors are essential in our attempts to explain the world, and in particular to grasp and explain novelty by analogy to things we already think we understand. A metaphor is meant to suggest an enlightening comparison, but economic metaphors are often more effective at revealing our outdated assumptions than they are at explaining modern events. (p. 158)

Foster is positing that modern business is too novel for our brains which hold onto certain beliefs and expectations of the world that better fit the primitive societies we used to live in.

The problem is that when it comes to economics, not only are the fundamental concepts involved novel and complex, but the subject matter is profoundly intertwined with moral assumptions about human relationships. Inappropriate metaphors might be fondly embraced and propagated not only because they are morally satisfying but because they are politically useful. (p. 159)

As I’ve said before, we do not come into this world as blank slates, but we have some built in code that we apply to the world as we grow.

If that is true, Foster is postulating that inbuilt programming can cause us to see the modern world through a lens that makes it hard to understand how things really work. And, as he said in the quote above, that can also leave us vulnerable to exploitation by power seeking leaders.

Foster notes it is not just that we “misinterpret commercial relationships” in a variety of different ways, but that we only misinterpret them in a negative way as brutal and aggressive. (p. 159)

I believe that this common way of misunderstanding supports the thesis that we often still think — or, more precisely, fail to think — on the basis of hunter-gatherer assumptions. (p. 159)

Erroneous Economic Ideas

Foster turns to economist David Henderson’s idea of do-it-yourself-economics (DIYE). (p. 161)

DIYE beliefs are “the economics of Everyman.” (p. 161) These are the assumptions people hold without even realizing it.

- Unreflecting centralism is the idea the economy needs to be planned by governments

- Self-sufficiency is the preferred ideal

- Domestic manufacturing should be aided by government policies

- Exports are better than imports

- Economic output is fixed

- Inventions that lead to less labor means lower long term employment

Introductory economic classes are all about counterprogramming these very beliefs. I never knew where they came from. I thought it was either lack of time put to thinking about it or having been told some incorrect information by other teachers or the media.

However, this idea of DIYE means these are more ingrained than I realized which explains why they are so hard to shake out of a substantial minority of the students.

If it were just lack of information or bad information, a good argument should sway people more. Since experience shows me that is not the case, I am inclined to believe Foster has raised an interesting point.

Most people — including not merely “practical men” but policy-makers — don’t derive their ideas about economics from economists at all. Those ideas are intuitive and mostly erroneous. (p. 160)

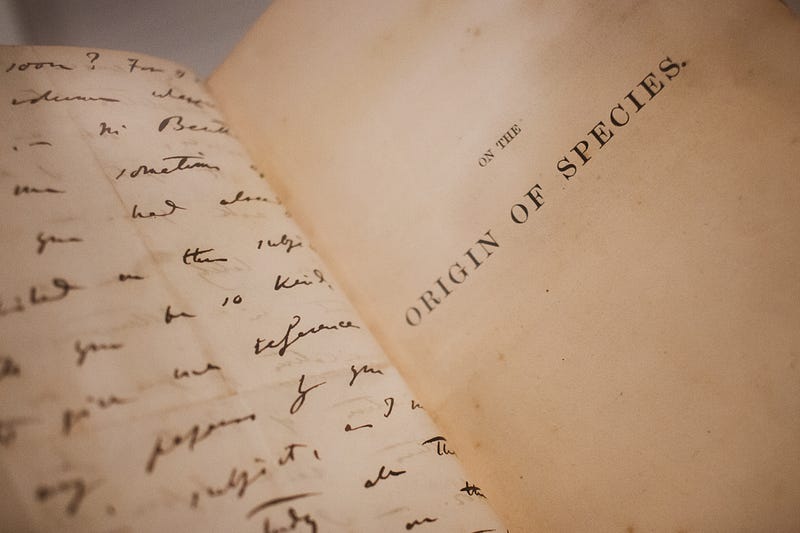

Adam Smith was specifically arguing against those first 5 intuitions in his book, The Wealth of Nations. He is the father of economics on a whole new level, I now realize. He was the first to spell out how economists think contrary to intuition.

And as Foster notes, thinking like an economist is heartily rejected by many because

…so reflexive are these largely spurious ideas that it simply does not occur to people that they might be both wrong and dangerous, and that there might be an alternative way of thinking. (p. 162)

One of the struggles is that economics is examining impersonal commercial transactions. When we are at the store, we have no understanding of all the people and steps required to get the products we buy to the shelf. Our minds are made for a world where we are in a small tribe or village of people who we have relationships with.

Economist Friedrich Hayek noted we live in a “two-world tension,” as Foster quotes him. (p. 164)

“Man’s instincts, which were fully developed long before Aristotle’s time, were not made for the kind of surroundings, and for the numbers, in which he now lives. They were adapted to life in the small roving bands or troops…” (p. 164)

Likewise, Karl Popper noted that people struggle with these two worlds.

Popper maintained that Western civilization had still not recovered from the shock of its birth: the transition from a “closed” tribal society “with its submission to magical forces, to the ‘open society’ which sets free the critical powers of man.” (p. 165)

Foster brings back Ayn Rand to note that she, too, highlighted the two-worlds problem, but since she believed that people were born with a blank slate, she did not really pursue this idea.

She did comment though that the idea of redistribution of wealth could be seen as based on the idea that wealth is an “anonymous, tribal product” that makes it a collective good that should be shared, which could be appropriate for a hunter-gather tribe. However, she said it was was obscene to apply that to a modern industrial economy that is based on individual achievements. (p. 166)

I will delve further into specific economic mistakes Foster says we intuitively make and the consequences of those errors in the next blog.

Reference: Foster, Peter, 2014. “Do-It-Yourself Economics” Chapter 8 of Why We Bite the Invisible Hand, Pleasaunce Press.