A Discussion of Peter Foster’s Why We Bite the Invisible Hand Chapter 7 “Darwin’s Dangerous Idea”

As Foster continues to explore reasons people tend to dislike capitalism despite the wealth it has generated the past couple of hundred years, he turns to the ideas of Charles Darwin and natural selection.

Essentially, Foster is holding to the idea that our brains have not changed from the hunter gatherer days when much of our heuristics were created, and yet we obviously live in a very complex modern world. He is suggesting that it is this mismatch that may be at fault.

The Idea of Natural Selection

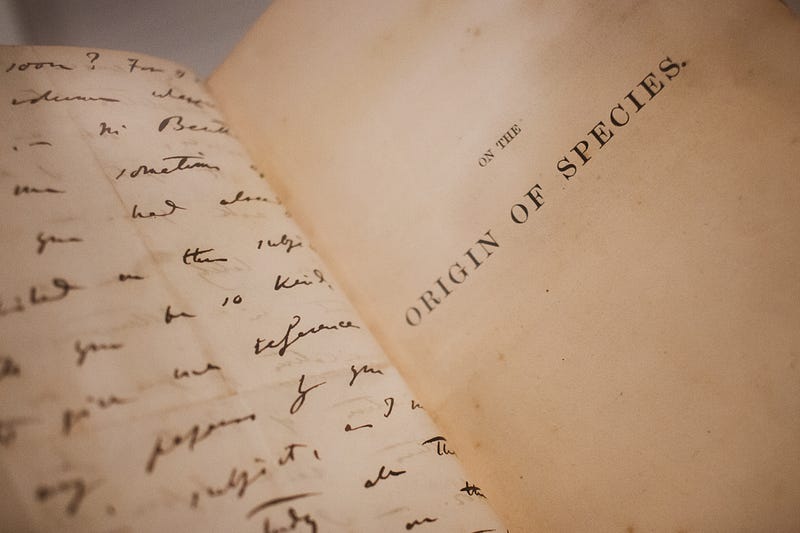

While Charles Darwin is credited with the idea of evolution and natural selection, it was not completely original to him. Like most ideas, it was part of the ongoing academic discussion.

His own grandfather, Erasmus Darwin was a botanist who hunted fossils and believe in evolution. (p. 139) And Charles Darwin would have been well acquainted with his ideas because he wrote his grandfather’s biography.

When he could not live up to his father’s wish to become a doctor, Charles Darwin was sent to study at Christ’s College in Cambridge with the intent he would have a career in the church. (p. 139)

He ended up following in his grandfather’s footsteps as a naturalist. Today, that seems like a contradiction, but then it was not.

The study of natural history was hardly meant to be the route to intellectual upheaval. Indeed, it was an approved pastime for the clergy, whose number Darwin had almost joined. Everywhere naturalists looked, they saw evidence of a marvelously complex “intelligent design.” (p. 140)

This is the idea of general revelation that we can see God’s power and existence by observing the order and intricacy of nature.

And yet, the ideas behind evolution have been around for a long time. Prior to Christianity, something like evolution seemed a possibility to ancient thinkers.

The idea that humans had somehow evolved from the primeval slime (as suggested by grandfather Erasmus) was as old as the Greek philosophers, although hardly popular with the church since it clashed head-on with Biblical accounts of Creation. (p. 140)

While the ideas were not new, Darwin did have an experience few of his day did that helped contribute to his work, On the Origin of Species.

A professor from college recommended Darwin as the naturalist to sail with the HMS Beagle on a five year tour of the southern hemisphere which allowed him to collect samples, gather observations, and see the similarities of species in similar environments spaced far apart. (p. 139)

He did write an account of his findings from the voyage, but then he retired from public life to live the life of an English gentleman. Foster says he continued to ponder the idea of evolution trying to find a mechanism to explain how it could work.

He pieced together various ideas of the day. Foster says Darwin had studied Adam Smith at Cambridge and liked the idea of “an emergent commercial natural order” in commerce, the order provide by the Invisible Hand.

Thomas Malthus was unfortunately another influence. I don’t know if Darwin was a Malthusian, but he did recognize the idea of a struggle to survive. (p. 142)

In such a struggle, Darwin realized, mutation might lead to an advantage that could mean the difference between life and death, and being the end of the biological line. (p. 142)

It is hard to say if Darwin would have ever published his book since he mulled the ideas for 20 years. But in 1858, Alfred Russell Wallace, a self-taught naturalist, sent Darwin an article he had written outlining his theory of evolution. He had read Darwin and other scientific works so presumably he wanted feedback.

Darwin reportedly saw the similarities with his own unpublished ideas, and he consulted colleagues of his on how to proceed. They decided that Darwin should present Wallace’s paper alongside excerpts of Darwin’s writings as a paper with Darwin and Wallace’s name on it to the Linnean Society, which would be like publishing in a prestigious journal today.

Wallace was not consulted on all this, but as a a very junior academic, he would not have been able to stop it anyway! And Darwin’s prestige is then granted to him, and he was able to have a good career as a result.

The Impact

Darwin well knew this theory would be a challenge to Biblical authority. The philosophical and scientific advances that had come from the Age of Enlightenment that just preceded his time were largely made by those who questioned the church.

Evolution took it one step further postulating an alternative creation story. And yet, over 150 years later, Foster cites a 2001 Gallup poll that shows true believers in evolution were rare in America. (p. 143)

- 45% agreed “God created human beings pretty much in their present form at one time within the last 10,000 years or so.”

- 37% believed God worked through evolution

- 12% believed humans evolved from other life forms without any involvement from God

Since I am not a scientist, I assumed that the evolution theory was more or less proven when I was growing up. But when I looked into it later, it seems like it always hits a point of a lot of handwaving that makes it seem like they don’t really have answers.

A classic challenge is how complex systems, like the human eyeball, could evolve. Mutations on making a species bigger or smaller over generations seem easy enough to believe. We can see what we have done to the wolf with all the different dog breeds.

But none of those dog breeds created new information. All the traits we see were in the original ancestor; we just changed their expression. This sort of breeding would not create some new complex feature that needs dozens of simultaneous random mutations to occur at the same time.

I heard another challenge in an interview with mathematician David Berlinksi that he said Darwin was aware of.

If you consider dogs, at some point he says you had to have the first dog in the species. But its parent was not a dog. The transition from wolf to dog was too abrupt, too discrete to use a math term. There is a continuity built into the theory that obviates the creation of new species.

The poll numbers above show more than half the people have a role for God, but looked at another way, almost half have a role for evolution. And though only 12% are tossing God out, that is in fact what has permeated the culture.

The consequence of believing our creation is a result of random mutations has been a devaluation of human dignity and of the value of life.

Foster does not engage with this problem, but instead he focuses on the idea that the human mind developed in a very different world than we currently live in.

He cites Steven Pinker in his book, How the Mind Works.

…our basic cognitive faculties and “core intuitions” are “suitable for the life-style of small groups of illiterate, stateless people who live off the land, survive by their wits, and depend on what they can carry…[Thus] for many domains of knowledge…people show no spontaneous intuitive understanding.” (p. 151)

That is, one example Pinker gives is how our minds are fooled by television. That a rational mind would realize they are just looking at digital images of people that are not actually there, yet we get caught up in our emotions, letting the stories evoke our sympathies. (p. 154)

Foster then notes that Adam Smith’s idea of benevolence, that we have sympathies for our fellow man, is just an adaptation we acquired over the years because it was socially beneficial at helping our survival.

Foster will extend this idea of social evolution to develop further in a later chapter to explain people’s confused hostility to the institutions of modern life that we have built, such as free markets, that have allowed explosive improvements in our standard of living.

Not only are the moral sentiments infinitely messy in construction, but people appear designed to vehemently reject the notion that the recipe for their own sentiments might be a trick of evolution, or that certain moral assumptions might have been rendered inappropriate by rapid social evolution. (p. 156)

Foster seems to think he has found a potential answer by turning to evolution to answer his question of why people seem to hold inborn hostility towards capitalism. He is overlooking the consequences of his solution.

With a biblical worldview, we can explain it is man’s sinful nature that tends towards greed, envy, and other vices that could make us short sighted in our views towards capitalism. But if we repent and follow God, we find the moral strength and guidance to live in a way that generates the most fruit with the most joy possible in this broken world.

But with an evolutionary worldview, Foster can point to us developing virtues as a successful strategy over the years. Yet, if there is no God, there is no good or evil. There is no afterlife.

The virtues we have evolved to value according to Foster were those that worked in the societies of that time, which would have had some religious beliefs. However, the winning virtues will not remain the same in a secular culture. Without a belief in a higher power, the reasonable conclusion is to get as much as you can in this life now because at its root, evolution is a nihilistic worldview.

However, whether you attribute man’s nature to evolution or design, it is interesting to consider the mismatch between our inborn intuition and the modern economy we live in today. That is what we turn to in the next chapter.

Reference: Foster, Peter, 2014. “Darwin’s Dangerous Idea” Chapter 7 of Why We Bite the Invisible Hand, Pleasaunce Press.