A Discussion of Bourgeois Equality Chapter 29 “The Bourgeoisie Loved Measurement” and Chapter 30 “The Change Was in Social Habits of the Lip, Not in Psychology”

We continue Dr. McCloskey’s dive into why the Great Enrichment occurred when it did because the stories we tell ourselves shape the world of the future.

I am again combining two chapters that fit well together as a review.

Sociology not Psychology

The reasons economic growth exploded in some places starting around 1800 is debatable but the fact that it happened is not.

McCloskey’s entire book is exploring these reasons, but she is hardly the first to ask these questions.

One possibility is that something in people’s make-up changed — that there was a shift in individual psychology.

She offers up Max Weber who wrote in the 1950s about the Protestant work ethic as the source of the change. For example, he suggested the Protestants placed high value on thriftiness that allowed capital to accumulate. (p. 278)

McCloskey has shown in a previous chapter that the presence of capital is not what causes growth; it is instead the Bourgeois Deal that creates a system where knowledge and innovation can be allowed to flourish.

In this chapter, she offers another reason Weber’s thinking is wrong: people really have not changed.

“Buy low, sell high” is not a modern invention. It has been the basis of trade, always. And Homo sapiens has been a trader, always. (p. 279)

She points to the creation of money across societies and time as evidence people have always traded. We seem to have a need for something to serve as a medium of exchange and a store of value — two functions of money.

Whether it is cigarettes in a prison or certain stones or metals, we can find people turning to something to use as money to make trading easier time and again through history.

Appealing to the Protestant work ethic is insufficient as an explanation according to McCloskey because people did not suddenly become better in some way that allowed the Great Enrichment to take off.

A medieval English peasant was poor not because he was irrationally imprudent but because he lived in a society before the new ideas of liberalism, the Bourgeois Revaluation, the Bourgeois Deal, and the resulting Great Enrichment…But until the humans came to admire commercial versions of each [ethic], their economies crept along at $3 a day. (p. 283)

McCloskey says it is not that people psychologically changed, but instead it was a sociological shift — they changed what they thought about other people.

In other words, it was not a change in the psychology of the bourgeoisie that explained regional differences, whether inside England or between England, and say, France. It was a change, I affirm, in sociology…It was not what was instinctively inside people’s heads that mattered, since it varies little in humans (“I want more of that”), but what was on their lips, about other people (“Those wretched Browns, you know: they are such vulgar people, in trade.”) (p. 279)

Thus, McCloskey says the change that led to the Great Enrichment is a cultural shift that esteemed bourgeois virtues.

Love of Measurement

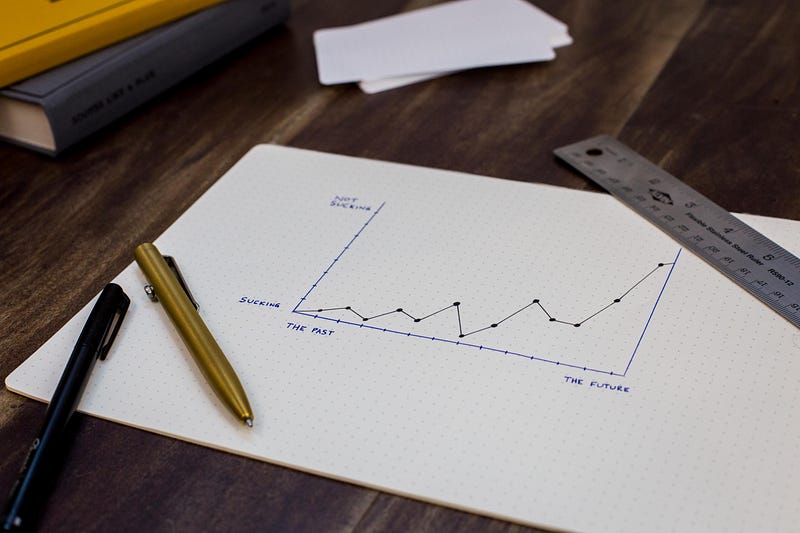

McCloskey offers other evidence of this cultural shift by tracing a change in the attitude towards measuring and quantifying.

Essentially, it is the rise of accounting to the point that Dutch mathematician suggested accounting could be applied to an entire nation just like it is for a business. (p. 271) While this section of the book has taken us back to 1700s England as we search for the origins of the Great Enrichment, the upcoming chapters will discuss how the Dutch were the first to esteem bourgeois values.

She tells the story of how this new quantitative thinking began to infuse political discourse through the story of a debate on whether or not to lift the ban on importing French wines into England in 1713. The arguments were not based on honor or national pride but instead on statistics, or, at least an attempt was made.

In June of 1713, the bill to relax the duties on French wine was rejected, purportedly on such rational grounds of numerical reasoning. The official statistics were dubious, the quantitative arguments on both sides nonsensical, the social accounting mistaken, the economics positively wacko. Yet a rhetoric of quantitative prudence ruled. (p. 273)

This turn towards numbers, statistics and quantifying arguments signifies the value of prudence that arises as society shifts towards esteeming the bourgeois.

What the modern fascination with charts, graphs, figures, and calculations does show, in other words, is that moderns especially admire prudence. It does not show that they always practice it. (p. 276)

Conclusion

I had heard over the years the theory that it was the Protestant work ethic that explained what McCloskey calls the Great Enrichment. But having read these chapters, I think her point that people-are-people is stronger.

She discusses Japan where until 1848 the “elite opinion scorned the merchant.” (p. 281) And in China, legal barriers to bourgeois advancement were lifted in the 800s but anti-merchant attitudes lingered into the 1900s. (p. 281)

The development is not simple, but the tendency is clear: a place must revalue the bourgeoisie or else it must become accustomed to economic stagnation. (p. 281)

That gets to the reason I am writing these reviews as well as to why I think McCloskey wrote her book. What we think about the bourgeoisie and their economic activities directly impacts our economic output.

If the reason we have enjoyed rising income is because society found positive value in prudence then we should be concerned when we hear voices now arguing against it.

That is, we could be going through another shift, but this time away from respecting the system of time tested betterments that gave us the Great Enrichment, which would likely be followed by a loss in productivity and a lower standard of living.

Reference: McCloskey, Deirdre Nansen, 2016. “The Bourgeoisie Loved Measurement,” Chapter 29 and “The Change Was in Social Habits of the Lip, Not in Psychology,” Chapter 30 of Bourgeois Equality, The University of Chicago Press.