A Discussion of “Studying the (Economic) Consequences of Populism”

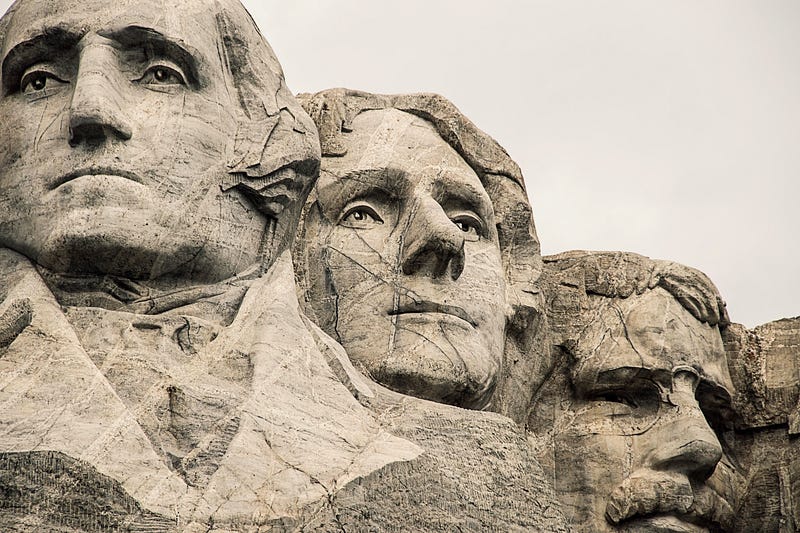

US President Donald Trump. Marine Le Pen, head of the National Rally party in France. Hugo Chavez, late president of Venezuela. Pablo Iglesias of the Podemos party of Spain.

They probably would not agree on much but they do have one thing in common — they have all been populist political leaders.

But if all these people with extremely different beliefs can be called populist, then what is populism?

Kaltwasser (2018) is willing to rise to this challenge because if we want to empirically study populism, we need a consistent definition. He is taking an “ideational approach” to defining and analyzing populism,

…a set of ideas that considers society to be separated into two homogenous groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’ and which argues that politics should be about respecting popular sovereignty by all means. (p. 204)

Two key elements of populism include

- A moral distinction between “the people” who are honest and virtuous and “the elite” who are tainted and fraudulent.

- A belief that politics should be about the will of the people that can conflict with “autonomous institutions” that are insulated from direct democracy and other checks and balances of the system.

This definition seems to touch on the danger of political populism discussed in a previous article. If these autonomous institutions are captured by the elite at the expense of the people, reforming them can provide a needed cure.

Without it, you can find yourself in a bout of political populism which can be removing the political checks and balances that prevent tyranny.

A Spoonful of Populism is the Medicine We Need

To study populism, Kaltwasser (2018) wants to use supply and demand, (p. 205)

- The politicians who push populism (supply side)

- Those in the electorate who subscribe to populism (demand side)

Researchers have studied the supply side by analyzing the speeches and writings by politicians around the world.

For the demand side, he says more research is needed but there is survey data that shows populist attitudes are widespread in various countries. Yet, it seems to lie dormant. That is, the surveys seem to indicate there is a tendency or willingness to support populism if it gets activated.

What could activate it?

Kaltwasser says “academics and pundits” tend to say it is bad economic times that awakens the dormant populism, but actually the empirical support of this popular opinion is not clear. (p. 205)

Some countries have populist movements even when the economy is strong while others suffered from the Great Recession without succumbing to a populist movement.

Another article I looked at examined this issue and found bad economic times tended to be a predictor of a populist movement if the trust in institutions is low.

Can Economics Illuminate the Populist Movement?

So then Kaltwasser asks, if the economy is not the cause, what is?

He proposes it is two interrelated political variables. (p. 205)

- How much the people have the perception the elite only care about themselves — as that perception grows, so does the demand for populism.

- The lack of ideological difference in the mainstream political parties — as the parties move closer to the center, and to each other, it creates room for parties on the left or right to claim both parties are essentially colluding.

Both of those factors then can predict the likelihood the demand for populism will grow, but what will the supply of populism look like?

Here, he concludes by describing the two kinds of populism — populism from the left and from the right. (p. 206)

- From the right, you see nativism characterized by limiting immigration and a tendency towards neoliberalism because the establishment is holding down the people through excessive laws taxes.

- On the left, you see a “reinterpretation of socialism” with the people seeking redress of the past socioeconomic policies of the past. It seeks an increase in economic regulations, taxation and redistribution and is hostile to business and their political allies.

Why does this matter? You cannot really study the economic consequences of populism if you lump both types together.

And while he has given us the two political variables that help grow the demand for populism, the type of populism supplied will depend on the side of the political spectrum that is responding.

You can end up with anti-immigration or anti-capitalism. Neither bodes well for the long term economic success of the country if these types of political populism take over. However, he does conclude with a note of optimism.

It could be the case that the long-term influence of populism will be related to its capacity to force mainstream political parties to adapt and therefore foster a process of ‘creative expression.’ (p. 206)

People turn to populism in part when they feel the current political structure is not working in their best interests but instead is serving its own, elite, interests.

The elites would fare better, and be more likely to maintain the system and their power in it, if they remember that they do need to be public servants, not political lords. When they forget, the door to populism cracks open and they can be escorted out.

References:

Kaltwasser, Cristobal Rovira (2018). “Studying the (Economic) Consequences of Populism.” AEA Papers and Proceedings, 108: 204–207.

By Ellen Clardy, PhD on .

Exported from Medium on December 15, 2022.