Part 2 of a Discussion of Peter Foster’s Why We Bite the Invisible Hand Chapter 11 “The Darwin Wars”

In the second half of the chapter, Foster turns to the origin of morality and posits it is not a recent innovation but something that is central to mankind.

In the period of prehistory and through most of history, an emphasis on acting for the “common good” was essential to group survival in a world of intergroup predation. The flip side of internal cohesion was the tendency to demonize the “other.” This helps explain the “us-and-them” orientation of human beings, and why we tend to apply different moral standards to the “in group” and the “out group.” (p. 243)

Foster is saying then that our moral sentiments are something deeply ingrained. They are the programming code we are not even aware of being there and as such are not examined but taken as truth.

In the last blog, Foster asserted the field of sociobiology was morally unified, which left them blind to their own biased assumptions.

Economist Friedrich Hayek examined the origin of our morality in his book, The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism. (p. 243)

He noted Adam Smith’s writings were the first to recognize we were moving into a new way of organizing human economic interactions with the rise of capitalism, but this led to a clash with our inborn morality.

Those new methods inevitably clashed with more slowly changing moral values, which had often become embodied in religion, but which were present even among those who felt themselves free of religious “superstition.” One reason that moral sentiments ae slow to change is that they are adaptively “designed” so that people believe them to represent transcendent values. (p. 243)

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt tackled this clash in his book, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. He hoped his book would take out some of the intense hostility in our culture war between the two sides. (p. 246)

The problem, he suggested, is that our rational mind is like a small, somewhat conscious rider on a very large subconscious elephant. The rider doesn’t guide the elephant, he acts as its press secretary, justifying what the elephant wants to do, and all the while imagining it was his own idea. (p. 246)

The book takes that as its central metaphor and discusses how they tested the hypothesis on people around the world. I read it a while back and do recommend it to anyone interested in how we essentially delude ourselves confidently!

Thus, the Right and Left have elephants with different ideas, and their riders are focused on justifying their own elephants without realizing their unexamined assumptions about how the world works.

Haidt notes the elephants on each side have fundamentally different visions of human nature. (p. 247)

- The constrained vision of the Right: People are inherently flawed and need laws and institutions to keep it in check. Leaders are often corrupted by power.

- The unconstrained vision of the Left: human nature can be molded for the better if the proper institutions are put in place by good-intentioned leaders.

There, in a nutshell, is the culture war.

The Right sees the market as a constraining institution that drives the inherently flawed individual’s intentions into a better outcome, the essential conceit of the Invisible Hand metaphor.

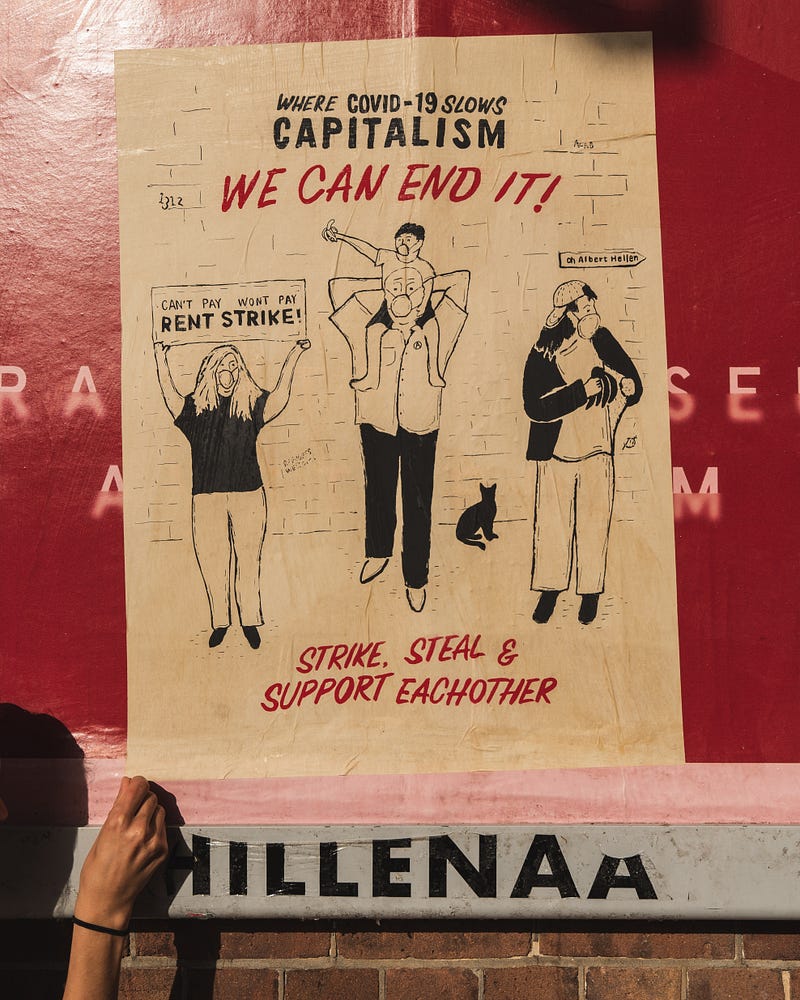

The Left sees the market as an inherently corrupting institution, and it needs to be replaced with better institutions more in line with a planned economy. The Invisible Hand is operating without a planner and doesn’t make sense; it sounds more like a religion.

While both sides believe in the importance of rules and institutions, the unconstrained view tends to imagine that all rules and institutions — and even human nature itself — can be remade by human intelligence, and that those who make these rules will not be corrupted by power. Such an orientation tends to not even countenance the possibility that the fundamental motivation of those who promote the unconstrained vision is power itself. (p. 247)

And that is how the two sides spend most of the time talking past each other.

This is why, for example, those on the Left have “treated market-oriented conservatism as a mental disorder.” (p. 246) Expecting a corrupt institution to not corrupt naturally good people seems insane to them. The Right though sees the institution as a check on naturally imperfect people.

If you are interested in reading Haidt’s book, it goes further into how our moral sense works. He posits we have five concerns: harm, fairness, loyalty, authority, and purity. (p. 248)

Each of these concerns comes from adaptive behaviors needed for society to function: caring for children, cooperation, group solidarity, hierarchical organization, and avoiding harmful contaminants. (p. 249)

Haidt claimed that the main difference between the Left and Right was that the Left tended to be obsessed with harm and fairness, while the Right had a more “balanced” level of concern across the five categories. (p. 249)

That explains the Left’s tendency towards, or comfort with, revolutionary reforms that could upend loyalty, authority, and even purity in the pursuit of more fairness and less harm. While the Right’s tendency is to slow changes that disrupt the current system.

Certainly, Haidt is offering a valuable contribution to our culture wars by potentially opening our eyes to the fact we are not seeing the world the same.

Ideally, then, we would slow down and try to see things the way the other side does, rather than resorting to name-calling.

Foster notes how hard it is to see our own blind spots by pointing out Haidt himself seems unaware of his own blind spots.

I certainly believe that Haidt was, and is, well-intended. The problem was that he still seemed to be carrying around much of the reflexive left-liberal baggage that (a) was blind to the Invisible Hand or claimed that its proponents were “fundamentalists”; and (b) tended to demonize “powerful” and allegedly feckless corporation as the justification for the “countervailing power” of big government, despite the fact that big government had historically been tyrannical, inept, or both. (p. 249)

Foster seems to be nearing his goal: gathering insight into the reflexive anti-free market thinking. Even someone like Haidt who is examining our inborn biases can be blinded to his own.

When the Right wants to leave the economy alone to be guided by the Invisible Hand, the Left sees that as folly. The market is an inherently corrupting institution to them, not the check on corrupt people as the Right says.

Surely smart people could devise something better. Let’s turn to the government, says the Left, to improve the outcome.

Then the Right recoils because they see the government as a collection of fallible people just as the businesses the Left wants to regulate are. As such, both can be corrupt to the Right.

Next chapter, Foster turns to the school of behavioral economics to weigh in on the source of anti-capitalist thinking. Its focus on irrational behaviors implies we should be concerned about the free market.

Thus, their message is well received by those in the government and policy circles whose unconstrained elephants think they know better how to run the economy.

Reference: Foster, Peter, 2014. “The Darwin Wars” Chapter 11 of Why We Bite the Invisible Hand, Pleasaunce Press.